“Hopelessness is the enemy of justice” Bryan Stevenson, author of Just Mercy.My last three posts concentrated on harm after harm from systems of racism that besieged Ferguson, Missouri’s African American residents from the time the first African American moved into town around 1970 until now. See Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

I confess it has been depressing to write these posts even though Ferguson’s place-based, systemic racism archetype confirmed nearly every major racial myth, fiction, and falsehood that I addressed in It’s Never Been a Level Playing Field: Overcoming 8 Racial Myths to Even the Field.

Yet, as I hinted in the first post, Ferguson has begun to change in the aftermath of Michael Brown Jr.’s murder and the local and national outcry for justice.

Because of the local protests organized by residents in Ferguson and supported by the national Black Lives Matter movement, the town—and the county in which it resides, St. Louis County—have made specific changes worth noting.

Because of tireless organizing by African Americans and the civic organizations they represent, Ferguson now has

Its first Black Mayor and first Black police chief.

A police force that is about 50% African American (in 2014, it was 6%)

A town council comprised of 6 African Americans in its 7-person elected body (at the time of Brown’s murder, it was the exact opposite, 6 Whites, one Black)

Police officers who are required to wear body cameras

A school board that was 86% White in 2014 is now 86% Black in 2024

St. Louis County elected its first African American St. Louis County prosecutor (Wesley Bell), a lawyer from Ferguson, who was a mediator during the Ferguson uprising.

Cori Bush, a Ferguson-based activist for racial justice after Brown’s murder, became the first member of Congress who had been active in the Black Lives Matter movement. She was elected to Missouri’s 1st Congressional District, which includes St. Louis City, Ferguson, and significant portions of St. Louis County.

She served two 2-year terms. In the 2024 election, Bell supplanted Bush to represent the District.

It’s unfortunate to say that very little of this progress would have occurred if not for Brown’s tragic murder,

His murder became a catalyst for the Black Lives Matter movement that activated a new and younger generation of racial justice activists not just in the St. Louis region but across the country. Had his murder not occurred, it’s far more likely, at least in Ferguson, that little to no progress would have been made, as so little had happened in the preceding half-century since African Americans were allowed to be Ferguson residents for the first time.

Yet, out of tragedy, a multi-racial collaborative of leaders and activists has made impressive change.

Forward through Ferguson: A Catalyst for Lasting Positive Change?

In November 2014, Missouri Governor Jay Nixon appointed an independent body of 16 commissioners to “provide an unflinching report outlining recommendations to address the underlying issues that contributed to the death of Michael Brown Jr.”[1]

Members included faculty and administrators from higher education, national and regional non-profit leaders, a superintendent of an adjacent school system, the Fraternal Order of Police, local attorneys, a community activist, a pastor, and a health care executive.

A razor-sharp quote from their report read:

“St. Louis does not have a proud history on this topic, and we are still suffering the consequences of decisions made by our predecessors. … the data suggests, time and again, that our institutions and existing systems are not equal, and that this has racial repercussions. Black people in the region feel those repercussions when it comes to law enforcement, the justice system, housing, health, education, and income.”[2]The commission made several dozen priority recommendations—on law enforcement and court reform, school system improvement, greater access to health care, expansion of early childhood education, increases in affordable housing, and greater accountability for predatory lenders—that they acknowledged would be difficult to implement.

Historically, Blue Ribbon Commission reports in the U.S. generate initial excitement, but implementation fails, lags, or never gets enacted. The report itself gathers dust on a shelf alongside reports from yore.

Key leaders and activists in Ferguson and St. Louis County were committed to ensuring the critical ideas and thrust of the Commission’s work did not collapse and disappear.

Since Ferguson sits in a region (St. Louis County) and within a dysfunctional ecosystem where racial injustices and inequities are too commonplace, stakeholders decided to make commitments and investments that focused not just on Ferguson but the city of St. Louis and other impacted local municipalities as well.

Several local, regional, and national foundations provided seed funding to create a regional non-profit, Forward Through Ferguson (FTF), in late 2015, a month after the Ferguson Commission’s report went public.

FTF was created to carry on the legacy of the energetic activism and advocacy that occurred for more than a year after Brown Jr.’s murder (400 days)—and to ensure that the 189 calls to action from the Commission’s report remained front and center.

Since 2016, FTF has served as a non-profit catalyst for lasting positive change in Ferguson and the region, centering impacted communities and mobilizing “accountable bodies to advance racially equitable systems and policies that ensure all people in the St. Louis region can thrive.”[3]

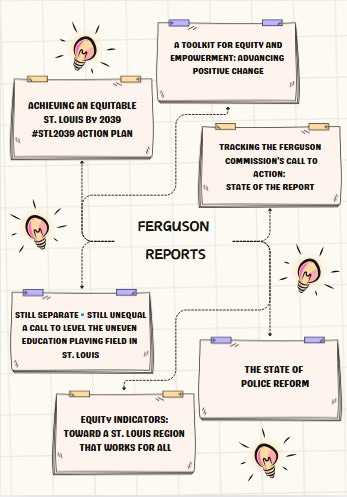

To detail the progress made beyond what I cover below would require an entirely separate post. But if you want to dig much deeper, the graphic below shows the six reports that tell the deeper story and chart the uneven progress made thus far. Below the graphic are links to the reports.

Equity & Empowerment Toolkit, Urban League of Metro St. Louis, 2017.

#StL2039 Action Plan. Achieving an equitable St. Louis by 2039 (2018 report)

Commission's Call to Action, August 2018.

Uneven Education Playing Field and its accompanying website - https://stillunequal.org/.

Police Reform, part of the State of St. Louis Series, September 2019.

Equity Indicators, 2018. Plus, the United Way of Greater St. Louis’ equity indicators dashboard for the St. L. region - Indicators Dashboard.

Commission Playbook. The Only Way Forward is Through: The Ferguson Commission Playbook, a summary of the commission’s work from Fall 2014 to Fall 2015,

In 2020, The Deaconess Foundation, in collaboration with FTF and Missouri Foundation for Health, launched a $2 million regional, racial healing and justice fund (with financial support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) to invest in community organizing and arts it says will heal trauma and change conditions that reinforce systemic racism.

From 2021 to 2023, the Fund invested nearly $1.7 million in dozens of organizations in the St. Louis region. In 2023 alone, it supported 42 Black and Brown-led organizations.

Recipients and their focus areas in 2023 included:

Racial Equity, Empowerment, and Social Justice

Healing and Urban Farming

Youth Programming and Development

Education and Literacy

Arts

Maternal Health and Pregnancy Support

Community Engagement[4]

As impressive as these philanthropic efforts have been, the original Commission report called for a 25-year endowed and managed Racial Equity Fund to support initiatives promoting racial healing and justice.

The past three years have served as a pilot program for the Racial Equity Fund, but fundraising to endow the fund has been an ongoing struggle. It remains to be seen whether the Fund can become a model locally and nationally for “responsive philanthropy that prioritizes the needs of marginalized communities while addressing systemic barriers that perpetuate racial disparities.”[5]

Progress in K-12 Education: Some Good News

Spurred by the protests in Ferguson in 2014, two 11th graders in the Ferguson-Florissant school district formed and led The Vision, a student group, to focus on improving their high school. As a result of their activism and of the activism of stakeholders inside and outside the school district, essential changes in the past 10 years have included:

Achieved a 92.3% graduation rate in 2023-2024, surpassing 90% for the sixth consecutive year and a significant increase since 2014[6]

Added its first Advanced Placement classes at the high school

Invested in a graduate-level certification program for teachers in elementary math (60 District teachers have achieved advanced math certification)

Hired a new superintendent, Joseph Davis, who became the 2nd Black superintendent of schools in the system’s 40 years. The school district hired Davis after suspending the first Black superintendent without explanation after five years of service.[7] Brown has provided inspirational and stable leadership for the school system for the past decade (2015-2024, an unusually long tenure for a superintendent in the U.S.).

Significant progress on the state of Missouri’s Annual Performance Report (APR), attaining a 66% score in 2022, 69.4% in 2023, and 73% in 2024. These scores have risen incrementally each year throughout Davis’ tenure.[8]

The District’s seven-member school board, which had 6 White members and 1 African American member when Brown was killed, is now 6 Black members and 1 White member after a victory in an American Civil Liberties Union lawsuit that helped make it easier for African Americans to win seats on the Board, overturning a voting process that for decades allowed White Ferguson voters to have too much influence on the elections of White Board members.[9]

Criminal Justice: The Good News (with many grains of salt)

As you learned briefly above, since 2014, the town has had its very first Black police chief in place 20 years since it became a majority Black jurisdiction. Its police force, which in 2014 was more than 90% White, is now about 50% African American.

The force also now has a mandatory body camera policy for all its police officers when out in the community. The police force also has implemented mandatory de-escalation and crisis intervention trainings for its police force plus community-oriented policing.[10]

Effective de-escalation training focuses on reframing officers' roles as “active listeners who gather intelligence to resolve situations by building rapport without resorting to force”[11]. It works best when officers’ supervisors are also trained.

Many of those changes resulted from the U.S. Department of Justice’s scathing 2015 report on the town’s police department and court system. Subsequently, the DOJ placed the police department under a consent decree in 2016 after it found that Ferguson police had violated the First, Fourth, and 14th Amendments, among many other violations.

Remember how municipal police forces and courts operated in the region (and Ferguson) in 2014: a pay-to-play system that criminalized poor residents and exploited them for money excessive ticketing, fines and fees, and warrants?

According to Arch City Defenders (ACD), a legal advocacy organization that combats the criminalization of poverty in communities of color, Ferguson and other parts of North St. Louis County have seen their rates of ticket issuance, warrant issuance, and municipal court revenue decline by half over the past ten years![12]

Mind you, many of these decreases occurred because ACD filed, litigated, and settled seven federal class action lawsuits in the region, including in Ferguson.

The bad news here, however, is that Black motorists (and residents with low incomes) are still disproportionately stopped throughout northern St. Louis County including in Ferguson.

In its assessment of municipal court reform in the region, ACD reports that because of “a multifaceted and sustained effort, there are tens of thousands fewer people who are ticketed, fined, and subjected to arrest by municipal police and courts every year. There are tens of millions of fewer dollars transferred annually from ordinary residents to municipal courts.”[13]

Yet, ACD comes to a sobering conclusion: “Those ensnared in the trap of municipal police and courts still face a system that punishes and exacerbates poverty, with no identifiable benefit to public safety or community wellness.”[14]

The local team monitoring Ferguson’s compliance with the DOJ consent decree found that the hiring of a Black police chief (Troy Doyle) in early 2023 accelerated some areas of change that had lagged for several years before his hiring. In particular, the chief hired a new training coordinator to design and deliver in-service training on new policies and practices.

However, activist community members did not appreciate that town leaders failed to consult with the community before hiring Doyle.

One final positive: the uprisings in Ferguson (and elsewhere) in 2014 led to the Washington Post creating a police shootings database to help national and local policymakers have a much more complete and accurate idea about how common police shootings are: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/.

Ferguson: Prospects for Continued Change

It’s important to remember that the Ferguson protests lasted more than 400 days. That activism still sparks the significant but slow-moving changes we’ve seen over the past ten years.

Much more has happened than I have recounted here.

Undoubtedly, this is meaningful progress.

It only occurred because of the vocal racial justice advocacy of the burgeoning Black Lives Matter movement back in 2014-15 and the new cadre of activists in the St. Louis region that movement birthed.

It could have been a moment of national reckoning, presaging what happened after George Floyd’s police murder. Yet, aside from the federal DOJ's role in publishing its scathing report and the consent decree that followed little change or reform occurred elsewhere.

In our divided, polarized times, the responsibility for important social and economic reform across policy areas in Greater St. Louis has remained—and will likely remain—almost exclusively with leaders and activists from Ferguson, the city of St. Louis, and St. Louis County.

Will change continue to march forward in Ferguson and St. Louis? Some leaders and most activists say there’s no choice but to continue moving forward.

Zach Boyers, CEO of US Bancorp Impact Finance (and a Forward Through Ferguson co-chair), said it eloquently and sharply at a 10-year commemoration of Brown Jr.’s killing.

It is critical to “maintain and sustain a level or urgency … To get to a place where outcomes, life outcomes, health, wealth, all of it is no longer predictable by race; we’re not anywhere near there. We need to continue to sustain that commitment to urgency,”[15]

Ferguson—and St. Louis—still have a long way to go to achieve any semblance of a level playing field. However, community members, activists, and leaders are tackling the massive changes required, head-on

“The best way to honor the Ferguson Uprising is never to place it in our rearview mirror. It took centuries for the current political landscape to form, and it will take all of us placing our hands on the plow to till the soil for the world we dream of to grow.”[16] Brittany Packnett Cunningham (Ferguson activist), 2019.

As the Ferguson Commission report stated a decade ago, “the only way forward is through.”

Footnotes

[1] Karishma Furtado and Kira Hudson Banks, “A Research Agenda for Racial Equity: Applications of the Ferguson Commission Report to Public Health,” American Journal of Public Health, November 2016, 106(11), pp 1926-1931, Journal article link.

[2] Jason Rosenbaum, “Ferguson Commission Shines Light on Racially Divided St. Louis,” NPR, September 14, 2015, https://www.npr.org/2015/09/14/440139685/ferguson-commission-shines-light-on-racially-divided-st.-louis.

[3] Forward Through Ferguson website..

[4] “St. Louis Regional Racial Healing + Justice Fund Invests $800,000,” St. Louis Community Foundation, July 28, 2023, https://stlgives.org/st-louis-regional-racial-healing-justice-fund-invests-800000/.

[5] Annissa McCaskill and Jia Lian Yang, “10 years after Ferguson: How philanthropy can bridge funding gaps for Black and brown-led organizations, Responsive Philanthropy, October 2024, pp. 4-6.

[6] Ferguson-Florissant Makes Continued Improvements in Academics, School District site.

[7] Denisa R. Superviille, “One Year Later, Ferguson Schools Poised for Change,” Education Week, September 16, 2015, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/one-year-later-ferguson-schools-poised-for-change/2015/09.

[8] Ferguson-Florissant Makes Continued Improvements in Academics, School District site.

[9] List of Board of Education members for Ferguson-Florissant school district, https://www.fergflor.org/domain/3286

[10] Madison Holcomb, “A decade after Michael Brown’s death, people in Ferguson see change and more work ahead,” St. Louis Public Radio, August 8, 2024, https://www.stlpr.org/culture-history/2024-08-08/ferguson-panel-reflects-10-years-michael-brown-jr-death.

[11] Brian Tich, “What Works in De-Escalation Training,” National Institute for Justice, April 18, 2023, https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/what-works-de-escalation-training.

[12] “Reflecting On A Decade Of Reforms Post-Ferguson, Archcity Defenders Urges Consolidation Of St. Louis’ Municipal Courts,” ArchCity Defenders, July 25, 2024 https://www.archcitydefenders.org/decade-of-reforms-post-ferguson-archcity-defenders-white-paper-debtors-prisons/.

[13] Ibid.

[14] In the Rearview Mirror: St. Louis’s Municipal Courts After a Decade of Reform and Regress ArchCity Defenders, July 2024, https://www.archcitydefenders.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ACD-White-Paper-In-the-Rearview-Mirror-7.25.24-1.pdf, p. 15.

[15] Madison Holcomb, “A decade after Michael Brown’s death, people in Ferguson see change and more work ahead,” STLPR, August 8, 2024, https://www.stlpr.org/culture-history/2024-08-08/Ferguson-panel-reflects-10-years-michael-brown-jr-death.

[16] “In the Rearview Mirror: St. Louis’s Municipal Courts After a Decade of Reform and Regress,” ArchCity Defenders, p. 1.