The Fergusons of America, Part 2:

Ongoing Systemic Racism & Segregation Leads to Profound Economic and Health Inequities

This is the second of a three-part series about Ferguson as a poster child for systemic racism and continued White domination. This post explores how Ferguson's racist history has led to the profoundly unequal outcomes that we see in too many American cities and suburbs for income, wealth, health, and environmental injustice.In my first post on Ferguson earlier this week, we briefly explored the origins of Ferguson as an all-White, sundown town and its immediate, predominantly Black neighbor—Kinloch.

We also explored how Ferguson’s racial demographics changed dramatically from 1970 until now, shifting from 1% to 72% Black and from 99% to 21% White over that half-century, and how, as the racial demographics changed sharply, the White power structure essentially remained in town politics (a White mayor and nearly all-White council), school system (White superintendent), and police force (again, predominantly White), while maintaining racial segregation in almost all of its neighborhoods.

This has been the reality of Ferguson; and of way too many places throughout America: in towns, metro areas, counties, regions, and states.

The troubling trajectory of Ferguson is rooted in our nation’s DNA. And it has disturbing consequences for African Americans across almost every policy area.

The Challenges of Building Wealth: Where Blacks Live in Greater St. Louis Matters

Thus, it should not be shocking that if we are to understand Ferguson, in part, we must understand St. Louis County and its metro area.

The St. Louis metro area ranks as the 7th most segregated region out of the 48 largest metro areas in the country, behind only Milwaukee, New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and Buffalo. In 2019, the St. Louis region ranked in the top 10 nationally on racial disparities between Blacks and Whites for:

poverty (8th)

unemployment (8th)

income (7th)

college graduation rates (10th), and

homicide deaths (8th).[1]

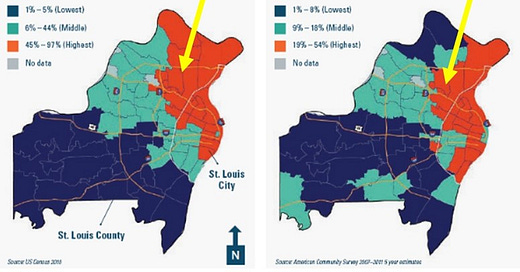

The maps below show where the African American population—and poverty—is concentrated in the county. They are almost mirror images except for the blue hump at the top of the right-hand map. The yellow arrow points to Ferguson’s location.

African Americans below the poverty line in the St. Louis region were almost 20 times more likely to live in concentrated poverty than Whites — the highest disparity among 50 large metro areas nationally, twice as large of a disparity as Nashville, Tennessee, which ranked second.[2]

Recent studies have revealed that cities and regions (like St. Louis … and almost all our Rust Belt cities) that had high shares of manufacturing employment in the past are more apt to have the highest rates of racial disparity today.[3]

In the St. Louis region, White households attain a median income of nearly $90,000 compared to Black households that make a little more than half that amount ($89,160 to $47,765 in 2024). This gap has widened by $12,000 since 2012.[4] Blacks in the region were also nearly three times more likely to be unemployed than Whites in 2017.[5]

In Figure 7 (data taken from the 2010 U.S. Census), you can see how the gap of nearly triple the unemployment rate between African Americans and Whites has stayed steady from 1980 until 2010. [I could not find comparative numbers for Ferguson only, but we can readily assume they are comparable.]

Because poverty rates are so high and unequal in the region, many African American households find it daunting to access the most obvious way to build wealth—by owning a home.

Across the St. Louis metro area in 2012, homeownership rates for White and Black residents were 74% and 42%, respectively. By 2017, the gap grew even wider to 77% and 41%, respectively (worse than the 29 percentage point racial gap nationally).[6]Where African Americans do own homes (mainly to the north of the county), it is almost always in communities where home values are low. In wealthier and Whiter neighborhoods, home values are considerably higher.

Like what happened across the U.S. in predominantly African American neighborhoods, the Great Recession and the foreclosure crisis that accompanied it were a disaster for many Black households in Ferguson. In 2013, 49% of the town’s homes were ‘underwater,’ meaning home values were below the mortgage payments owed. Too many homes that end up ‘underwater’ eventually lead to loan default or foreclosure.

You may remember that in the early 2000s, many “mortgage lenders targeted predominantly Black and Hispanic areas for the highest-risk, highest-cost types of mortgage loans. Many families that banks sold risky mortgages to had good credit, decent incomes, and everything else necessary to qualify for traditional long-term, fixed-rate loans. Yet, they were not offered those kinds of loans, but instead ‘steered into exotic and costly mortgages they did not fully understand and could not afford,’ the commission said.”[7]

The table below shows the vast disparity in median home values between Blacks and Whites in the city and county: White homes are valued 80% higher in the county and 76% higher in the city.

This has continued to wreak havoc on the financial health of too many Black Ferguson households and the stability of the neighborhoods they lived in.

In 2020, more than 20% of Ferguson’s population lived below the poverty line, well above the national average (12.5%). The very high majority of those were African American.[9]

An influential report, “Ferguson and Beyond,” concluded: “These findings reflect the historical legacy of the St. Louis region’s segregation regime and related disparities in the community.”[10]The historical legacy, as you know, doesn’t begin and end with economic inequities, however.

Health Inequities for Ferguson

The map below from 2014 shows us disparities in life expectancy (at birth) across the City of St. Louis and St. Louis County. As we can see, as you head due west and southwest, life expectancy in all cases exceeds 80 years old. In northern St. Louis, it’s 67, and in Pagedale-Wellston, a northwestern, majority Black suburb immediately outside the city, we see high rates of poverty with a life expectancy of 70.[11] Located about 3 miles south of Ferguson, Pagedale-Wellston is similar to Ferguson in both demographics and income levels.

The Ferguson Commission report issued in the aftermath of the uprisings in 2014 cites a life expectancy from the St. Louis County Health Department that is even more stark:

“In mostly White, suburban Wildwood, MO., the life expectancy is 91.4 years; in the mostly black, inner-ring suburb of Kinloch, MO., it’s 55.9 years. The reality behind those numbers is a complex, interconnected set of socioeconomic factors, including disparities in access to quality housing, healthcare, education and employment.”[12]Kinloch, remember, is the tiny, all-Black community immediately next to Ferguson. The life expectancy figures for both Kinloch and the Pagedale-Wellston provide an approximate sense (probably between 60 and 70) of what life expectancy would be for the lower-income, Black neighborhoods in Ferguson.

A frequently cited report published by Washington University and Saint Louis University in 2014, “For the Sake of All,” provides the best source for insight into health data for African Americans in Ferguson and St. Louis County.

The report found that both northern St. Louis City and northern St. Louis County have extremely limited access to pediatricians and that the infant mortality rate for Blacks is more than three times that of Whites. The chart below shows this disparity by deaths per thousand births.[13]

Receiving adequate prenatal care before their birth is critical to the long-term health of a child.

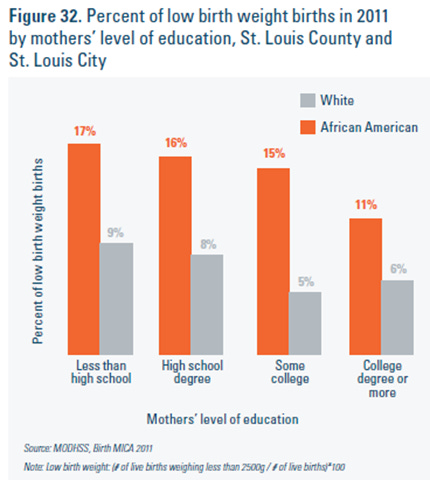

Figure 31 from the report below shows the racial disparities across a mother’s level of education between Blacks and Whites in the county and city. There is a significant disparity corresponding to every level of education in the region.

Figure 32 shows the disparities across a mother’s level of education that correspond with the percentages of an infant’s low birth weights. Low birth weights potentially negatively impact a child's long-term health into adulthood.

As you can see, the rate for African American women with a college degree is slightly higher than for White women with less than a high school diploma.

It is very disturbing that we see this vast difference.

We need to remember that:

“[l]ow maternal educational attainment is associated with poor health, which increases the risk for preterm births and LBW [low-birth weight]. Preterm birth and LBW, in turn, may increase children’s risk of impaired cognitive development, learning ability, and academic achievement. …

The highest rates of preterm births were reported mostly in zip codes in northern and eastern St. Louis City and northern St. Louis County. … In the city of Ferguson, the preterm birth rate was approximately 15% in 2012.”[14] (emphasis added)Unfortunately, the health inequities don’t end there. We must factor in environmental racism to understand the fuller story of inequities.

Health Inequities from Environmental Injustices

As it is in many metropolitan areas, asthma is a significant challenge in St. Louis City and northern St. Louis County for African American children. In fact, in the report Ferguson and Beyond, the authors indicate that:

“[a]sthma is the most common chronic childhood disease and is the primary reason for absence among school-age children. Asthma disproportionately impacts minority children in urban areas and children in poverty and, therefore, differentially shapes their opportunities to learn through missed school days and reductions in school connectedness. … In Ferguson, specifically, asthma rates among youth are three to five times those of central and western St. Louis County.” [15] (emphasis added)Central and western St. Louis County are wealthier and Whiter areas of the region. Figure 45 from “For the Sake of All” shows the racial gap across the region.[16]

A regional study by Washington University of St. Louis “found that 14% of St. Louis-area census tracts have elevated cancer risk linked to air pollutants. Risk is particularly great in areas with high levels of both racial and economic isolation — where people are less likely to interact with someone of a different race or economic status. … The strongest relationship exists in neighborhoods with high concentrations of black, poor residents, Ekenga said. …

People in those areas are five times more likely to face exposure to carcinogenic air pollutants than residents in White, middle- to upper-class income tracts. That disparity, she said, is “much stronger” than what she has seen in other cities.”[17] (emphasis added)

Where and how is Ferguson situated in the region?

Ferguson is nestled between three interstate highways (I-70 to the south, I-170 to the west, and I-270 to the north), each at most a mile away from the town. The airport sits approximately two miles away on the west side of I-170; Route 367 is also a major north-south commuter road.

Particulate matter from highway and airport emissions are significant sources of air pollution.

According to the American Lung Association (ALA), “[g]rowing evidence shows that many different pollutants along busy highways may be higher than in the community as a whole, increasing the risk of harm to people who live or work near busy roads.”[18]

The ALA cites a review of 700 studies globally on the health effects of pollution caused by traffic. This review found that traffic-based pollution causes asthma attacks in children and may cause other impairments to the lunch, as well as increasing the “likelihood of premature death and death from cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular morbidity.”[19] It also found that the people who faced the highest risks were adults with either diabetes or asthma.

If you remember the map on poverty at the top of this post, the highest poverty neighborhoods in St. Louis County are in northern St Louis City and predominantly Black communities in northern St. Louis County.

The blue arrow in both maps below (Figures C and D) point to Ferguson. We can see that Ferguson sits in the areas with the highest death rate for heart disease and in the middle range for cancer deaths.[20]

In the St. Louis region, African Americans also have death rates well above that of Whites for several of the most common cancers, including:

About 25% higher for lung cancer

Twice as high for colorectal cancer

About 50% higher for breast cancer

More than twice as high for pancreatic cancer[21]

African Americans in the region are more than four times more likely to be hospitalized for diabetes care than Whites.[22]

As you can see, the ongoing legacy of intentional, residential, and racial segregation has had—and still has—severe economic and health consequences for African Americans in Ferguson … and elsewhere.

In my next post, we’ll explore how this same legacy has impacted the quality of education and the perverted system of criminal justice for African Americans in Ferguson.Nearly all the figures, maps, and tables from this post come from an excellent 2015 report,

“For the Sake of All: A report on the health and well-being of African Americans in St. Louis and why it matters for everyone,” a joint publication of Washington University in St. Louis and Saint Louis University, July 31, 2015

... including Table 8, Figures 7, 12, 31, 32, 41, and 45, and the maps on poverty, heart disease, and cancer.FOOTNOTES

[1] “Where We Stand,” East-West Gateway Council of Governments (St. Louis), 2019, page 1 of Executive Summary.

[2] Jacob Barker, “Racial disparities in income and poverty remain stark, and in some cases, are getting worse,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 7, 2019, https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/racial-disparities-in-income-and-poverty-remain-stark-and-in-some-cases-are-getting-worse/article_9e604fc3-c47d-581e-95a2-5a2166011a17.html.

[3] “Where We Stand,” pp. 40-41.

[4] “2024 Demographics: St. Louis County,” Think Health St. Louis, https://www.thinkhealthstl.org/demographicdata.

[5] “Where We Stand,” East-West Gateway Council of Governments (St. Louis), 2019, p. 41.

[6] Alison Gold, “Segregation Levels in St. Louis Remain High, Study Finds,” Riverfront Times, May 25, 2018, https://www.riverfronttimes.com/newsblog/2018/05/25/segregation-levels-in-st-louis-remain-high-study-finds.

[7] Courier Newsroom, “Behind Ferguson’s unrest: Failed federal policy and the Black-White housing gap,” The New Pittsburgh Courier, August 26, 2014, https://newpittsburghcourier.com/2014/08/26/behind-fergusons-unrest-failed-federal-policy-and-the-black-white-housing-gap/.

[8] “For the Sake of All: A report on the health and well-being of African Americans in St. Louis and why it matters for everyone,” a joint publication of Washington University in St. Louis and Saint Louis University, July 31, 2015, p. 25.

[9] “Ferguson, MO,” DataUSA, https://datausa.io/profile/geo/ferguson-mo/.

[10] Brittni D. Jones, Kelly M. Harris, and William F. Tate, “Ferguson and Beyond: A Descriptive Epidemiological Study Using Geospatial Analysis,” Journal of Negro Education, Vol 84, No. 3, pp. 239-241.

[11] “For the Sake of All,” p. 27.

[12] “Fostering Racial Equity,” Forward through Ferguson, October 14, 2015, https://forwardthroughferguson.org/report/call-to-action/developing-an-analysis-of-individual-cultural-institutional-structural-and-internalized-racism/.

[13] “For the Sake of All,” p. 41 and p. 58.

[14] Brittni D. Jones, Kelly M. Harris, and William F. Tate, “Ferguson and Beyond: A Descriptive Epidemiological Study Using Geospatial Analysis,” Journal of Negro Education, Vol 84, No. 3, p. 244, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292177637_Ferguson_and_Beyond_A_Descriptive_Epidemiological_Study_Using_Geospatial_Analysis.

[15] Jones, et al, “Ferguson and Beyond: A Descriptive Epidemiological Study Using Geospatial Analysis,” pp. 245-246.

[16] For the Sake of All,” p. 50.

[17] Bryce Gray, “Effects of air pollution in St. Louis separate and unequal, study finds,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 2, 2020, https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/effects-of-air-pollution-in-st-louis-separate-and-unequal-study-finds/article_041595ff-438f-5e8a-8f5b-28d16ae076d8.html.

[18] “Living Near Highways and Air Pollution,” American Lung Association, https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/who-is-at-risk/highways.

[19] Living Near Highways and Air Pollution,” American Lung Association.

[20] “For the Sake of All,” p. 30.

[21] “For the Sake of All,” p. 49.

[22] “For the Sake of All,” p. 50.