Fergusons of America Part 3

Systemic Racism's Impact on Education and Criminal Justice for African Americans

This is the last of a three-part series about Ferguson as a poster child for systemic racism and continued White domination. This post explores how Ferguson's racist history has led to profoundly unequal outcomes in the realms of public education and criminal (in)justice.

In Part 1, we explored Ferguson’s racist history and how, decades after becoming a Black-majority town, Whites remained in control of all political and decision-making structures.

In Part 2, we looked at the often insurmountable challenges for Blacks in Ferguson to build wealth and bridge the racial health gap.Where Blacks Get Educated Matters

Michael Brown lived in what has commonly become known in the U.S. as a suburban ghetto in a dilapidated apartment complex rife with people living in poverty. His neighborhood’s median income in 2014 sat below $27,000. It was at the time among the top 10 poorest Census tracts in all of Missouri, where 95% of the residents were Black.

Months before Brown was murdered by police in 2014, he graduated from Normandy High School, which in 2012 had lost its state accreditation because of its depressingly low standardized test scores. Normandy High is in Wellston, a predominantly African American town a few miles south of Ferguson.

According to Missouri law, students in failed school districts can transfer to nearby higher-performing schools. However, Normandy High students could not transfer because the local school district had to pay tuition and transportation for each student transferring and couldn’t afford to.

Because the costs ran so high, the state waived the system’s accreditation, meaning no students could transfer. All students, including Michael, were forced to stay in a “failed” school.[1]

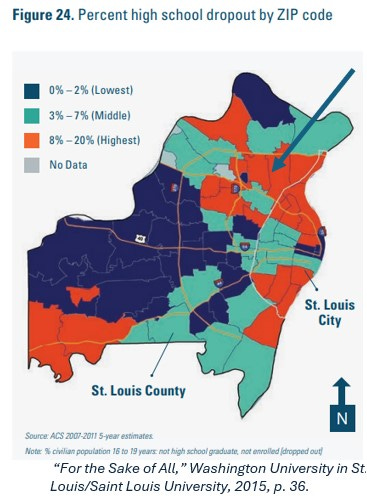

Michael was fortunate to graduate, but many of his peers did not. Although most high schools in the St. Louis region had graduation rates of 95% or higher, the dropout rate for the high school in Riverview Gardens (serving southeast Ferguson) was 8%. At Michael’s high school, it was nearly 22%. The blue arrow in Figure 24 above shows you the location of the schools.

The chart below, “Racial Disparity in Learning Environments,” demonstrates the disproportionate educational environment too many Black students in the region face every year, from a chronic absenteeism rate that is nearly 75% higher for Black than White students, a suspension rate that is almost six times higher; and an advanced placement enrollment rate that is more than twice as low for Black students than Whites.

These absentee, suspension, drop-out, and AP enrollment rates largely mirror what we see across every region in the country.

“Researchers have linked dropping out of high school to fewer opportunities for stable employment and related negative outcomes, including poverty, criminal activity and delinquency, and poor health.”[2]

Nationally, high school dropouts earn about $7,000 less per year than those who graduate.[3]

The academic proficiency for Ferguson-based high school students—whether attending Ferguson-Florissant or Normandy—looks as follows:

25-30% proficiency in English-Language Arts

9-28% proficiency in Math

14-26% proficiency in Algebra I[4]

Nationally, highly segregated public schools contend with challenging funding environments, more inexperienced and short-tenure teachers, and highly punitive environments that house students mostly from high-poverty neighborhoods and homes. For example, in the St. Louis region, “districts with a student population that is more than 50 percent black, over 20 percent of teachers have less than two years of experience; this is double the rate of districts with student populations that are less than 50 percent black.”[5]

The disparities in achievement for Ferguson students begin early in their academic careers. The school districts serving Ferguson in 2013 showed between 15-30% of Black students achieving below basic level by 3rd grade.

The same pattern shows up by 8th grade: in fact, Ferguson middle school students perform more poorly than African American students in St. Louis, one of the lowest performing urban school districts in the country (e.g., at 52% compared with 59% of students below basic in 8th-grade math).[6]

Far too many African American students in Ferguson are not receiving the education they need to succeed as they move into adulthood just as is true for too many Black students living in high-poverty school districts in the U.S.

The good news is that with the hiring of its first permanent African American superintendent (Dr. Joseph Davis) in the Ferguson-Florissant School District in 2015, the school system’s high school graduation rate climbed relatively quickly—from 81% in 2017 (when the system regained its state accreditation) to above 92% for three consecutive years, in 2020, 2021, and 2022.[7]

Its school board, which in 2014 had one African American member out of seven, now has six. This change only occurred after the American Civil Liberties Union won a court case in St. Louis County to change the process for how board members were elected.

Real change can occur even in the most challenging school districts when there is a genuine commitment to systemic and structural change. The changes in Ferguson occurred only after six decades of community struggle for better schools, more resources, and far better representation. And only after the crisis brought about by Brown’s murder.

NOTE: I could not locate data on Ferguson students who move on to postsecondary education.

The Ferguson Injustice System

The murder of Michael Brown devastated the local Ferguson community, and as we all found out about it, his death devastated many in the nation as well. It not only mobilized the Black Lives Matter movement in ways that continue to ripple through the country today, but it opened a window for White Americans to see how perversely many of our police and justice systems operate in towns and cities across America.

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) was called in to investigate not just Brown’s murder but accusations of rampant discrimination and racial bias in its police department and court system. In early 2015, the DOJ issued a scathing report.

Let us start by offering some genuinely startling statistics from Ferguson in 2014 (the year of Brown’s murder):

How do we explain all of this? There are no white sheets, white hoods, burning crosses, or riding through town in a horseback posse. But it looks suspiciously like day-to-day white supremacy … no?

Many Black residents in Ferguson have viewed the police as an occupying force. This is a common view about police in Black communities throughout the nation.

In its report “Forward through Ferguson,” the Ferguson Commission explained this perception further. “We heard from many Black citizens in the St. Louis region who do not feel heard or respected when they interact with the police or the courts. They do not feel that they are treated in an unbiased way. Rather, they feel that the presence of bias, a lack of respect, and an unwillingness to listen on the part of the police too often lead to unnecessary and/or excessive use of force.”[8]

The U.S. Department of Justice “found that Ferguson police and court officials had essentially applied excessive law enforcement tactics for the purpose of generating revenue off the backs of the town’s mostly black and impoverished residents.”[9] Was this unique to Ferguson? No. The report indicates that justice regimes like this in Ferguson are widespread in the towns and municipalities throughout St. Louis County.

Who gets targeted? In Ferguson in 2014, 25% of residents lived below the line, and another 19% lived below double the poverty line. The majority are African American.

Ferguson not only has its own police force. It has its own municipal code and its own court, as do at least 80 other municipalities in the county, each generating municipal revenue from fines and fees at outrageous levels, according to ArchCity Defenders, a St. Louis region legal advocacy organization.[10]

What were other critical elements of the DOJ report?

· “Ferguson police officers routinely violate the Fourth Amendment in stopping people without reasonable suspicion, arresting them without probable cause, and using unreasonable force against them.” [11]

· “[D]uring the roughly “during the roughly six-month period from April to September 2014, 256 people were booked into the Ferguson City Jail after being arrested at least in part for an outstanding warrant—96% of whom were African American. Of these individuals, 28 were held for longer than two days, and 27 of these 28 people were Black” (United States Department of Justice, 2015).” [12] (emphasis added)

The Ferguson Commission report identified the consequences to Ferguson’s Black residents with this predatory system in place:

“When someone is jailed for failure to pay tickets, the justice system has not removed a dangerous criminal from the streets. In many cases, it has simply removed a poor person from the streets.

In these cases, the justice system also removes that poor person from their family, from their community, and in many cases, from their job. These sentences can have long-lasting, widely-felt consequences, none of which directly impact community safety. …

When jail time results in three or four days of missed work, it can result in the loss of employment, making it even more difficult to pay mounting fines and consequently to find another job..”[13] (emphasis added)

Meanwhile, this predatory system of justice is a critical way for St. Louis County municipalities, especially those strapped for cash, to stay afloat.

Ferguson collected $2.6 million in court fees and fines in 2013 and was projected to collect more than $3 million in 2015 (nearly 30% of the city budget. It was so “efficient” at generating revenue in these ways that its court ranked 8th countywide for municipal court revenue.[14]

Unfortunately, the Ferguson police find themselves in an untenable position of issuing tickets in significant volume. If they fail to write at least 28 tickets per month, the city reprimands them. As a result of these perverse incentives, one policeman wrote more than a dozen citations for a single traffic stop. To make matters worse for Ferguson’s Black residents, the city court is only open 3 days a month. If they can’t afford to pay bail, the police hold them in jail until the next court session, which is often a week or more away. Thus, too many feel compelled just to plead guilty to exit jail more quickly.[15]

In Ferguson, you can be charged with offenses such as “manner of walking” (95 percent of such tickets were issued to African Americans), “failure to obey” (89 percent were issued to African Americans), and “failure to comply” (94 percent were issued to African Americans).[16]

The pattern of arresting Blacks in disproportionate numbers is common not just in the county but, as might be expected, across Missouri (a former slave state). The Missouri Attorney General’s office reported that since 2000

“African Americans have consistently been targets of racial profiling by law enforcement officers. In 2013, black Missourians were 66 percent more likely to be stopped by police, though they were not more likely than whites to be in possession of contraband. In fact, white Missourians were more likely to be found with contraband (34 percent) than were their black counterparts (22 percent). … The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) currently has a complaint against police in St. Louis County – where Ferguson is located – for racial profiling.”[17] (emphasis added)

Finally, in terms of incarceration, for St. Louis County from the most recent data I could find (2012), African Americans comprised about 23% of the county population but 54% of the adults in correctional facilities. In contrast, Whites comprised nearly 70% of the county population but only 44% of those behind bars.

The 8 Myths and the Fergusons of America

Richard Rothstein, in an excellent article he wrote before publishing his New York Times bestseller, The Color of Law, explains how places like Ferguson end up as profoundly racially unjust towns and cities.

“In St. Louis these governmental policies included zoning rules that classified white neighborhoods as residential and black neighborhoods as commercial or industrial; segregated public housing projects that replaced integrated low-income areas; federal subsidies for suburban development conditioned on African American exclusion; …

tax favoritism for private institutions that practiced segregation; municipal boundary lines designed to separate black neighborhoods from white ones and to deny necessary services to the former; real estate, insurance, and banking regulators who tolerated and sometimes required racial segregation; and urban renewal plans whose purpose was to shift black populations from central cities like St. Louis to inner-ring suburbs like Ferguson. …

Government policies turned black neighborhoods into overcrowded slums and white families came to associate African Americans with slum characteristics. White homeowners then fled when African Americans moved nearby, fearing their new neighbors would bring slum conditions with them.”[18]

The killing of Michael Brown was no anomaly.

Nor was the evolution from an all-White city to a majority Black city in a short, three decades, albeit still White run.

Nor was the level of poverty Blacks experienced in Ferguson or its neighbor, Kinloch.

Nor was the continuing segregation of schools under-serving Black students, nor the disparate health outcomes Blacks endure in Ferguson and Black neighborhoods nearby.

No, Ferguson is a normal occurrence in America, a result of malign neglect, carried out in the thousands of decisions made by thousands of White leaders and White-led institutions over the decades in just about every policy arena you can imagine.

All eight myths from my book come into play when looking at Ferguson. (The graphic of the 8 myths can be found at the end of this post)

Myth 1: America provides an equal playing field for all. When a majority African American town has White leaders running every part of government and dominates in the commercial arena, it’s clear that no playing field in Ferguson is level.

Myth 2: any segregation that Blacks experience is now strictly a result of individual choice. When most Blacks are restricted to living in a suburban ghetto that is chronically underserved with few amenities, we know this is not about personal choice.

Myth 3: if Blacks have worse health outcomes, it is due to their own poor choices. Racial segregation & high-poverty neighborhoods are no coincidence, nor are the health consequences that result—from racist systems, structures, & injustices.

Myth 4: everyone has the same opportunity to get a job/start a business/build wealth. When African Americans in the region (and in Ferguson) are 20 times more likely to live in concentrated poverty than Whites, the ability to find good jobs, pursue entrepreneurship, and accumulate property and wealth is astronomically difficult.

Myth 5: Black students have the same access to quality education as Whites. When Black youth attend failing schools, get suspended at 6 times the rate of Whites, and graduate at lower rates than students in higher-performing, better-resourced, & predominantly White districts, equal opportunity and access is an absolute falsehood.

Myth 6: Blacks are treated fairly by our criminal justice and policing systems. When you have rampant discrimination and racial bias in policing and court systems, when the police force is 94% White in a majority Black town, you have systems that are profoundly unfair and unjust.

Myth 7: we no longer restrict the rights and progress of Blacks. See the explanations for Myths 1 through 6.

Myth 8: systemic racism doesn’t exist; racism is simply individual acts of bigotry. See the explanations for Myths 1 through 7.

Correction: in my first post in this series, I indicated that Ferguson had lost 40% of its population since 2014, which is way off. The town has lost approximately 13% of its population during that time; I had the actual numeric decline right (from 21,200 to 18,500). For a town to lose even 13% of its total population in a decade is still a significant decline for any American suburb.

Footnotes

[1] Tracey Meares, “Ferguson's Schools Are Just as Troubling as Its Police Force: And the city won’t heal until we fix them too,” The New Republic, August 22, 2014, https://newrepublic.com/article/119169/ferguson-missouri-schools-are-just-troubling-its-police-force.

[2] Jones, et al, “Ferguson and Beyond: A Descriptive Epidemiological Study Using Geospatial Analysis,” p. 247.

[3] Jones, et al, p. 248.

[4] “For the Sake of All: A report on the health and well-being of African Americans in St. Louis and why it matters for everyone,” Washington University in St. Louis/Saint Louis University, 2015, p. 37.

[5] “Where We Stand,” pp. 3-7 of Executive Summary.

[6] “For the Sake of All,” p. 37.

[7] “Continued Progress as On-Time Graduation Rates Remain High,” Ferguson-Florissant School District, Link.

[8] “Forward through Ferguson: A Path Toward Racial Equity,” The Ferguson Commission, October 14, 2015, pp. 26-27.

[9] Christopher Zoukis, “Ferguson, Missouri Under Fire for Revenue-based Criminal Justice System,” Prison Legal News, December 8, 2016, https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2016/dec/8/ferguson-missouri-under-fire-revenue-based-criminal-justice-system/.

[10] ArchCity Defenders, www.archcitydefenders.org.

[11] Robert Longley, “Ferguson Riots: History and Impact, ThoughtCo, January 13, 2020, https://www.thoughtco.com/ferguson-riots-history-and-impact-4779964.

[12] “Forward through Ferguson, p. 31.

[13] “Forward through Ferguson, p. 32.

[14] Zoukis.

[15] Zoukis.

[16] Zoukis.

[17] Clarence Lang, “On Ferguson, Missouri: History, Protest, and “Respectability,” LAWCHA, August 17, 2014, http://www.lawcha.org/2014/08/17/ferguson-missouri-history-protest-respectability/.

[18] Richard Rothstein, “The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles,” Economic Policy Institute, October 15, 2014, https://www.epi.org/publication/making-ferguson/.