Writing consistently on the topics covered in It’s Never Been a Level Playing Field can be depressing and distressing for me. I imagine it can be for readers of this newsletter, too. I started this newsletter to complement the publication of the book and to continue to educate people (and myself) about what has contributed and continues to contribute to an unlevel playing field.

Although I will continue to spotlight the history and issues covered in the book’s eight myths, I plan to pause and provide positive news as well occasionally. That’s my focus in this newsletter issue.

Today’s issue will focus on the work of the Urban Institute, a think tank based in Washington, DC, that was a critical resource throughout my four years of research on race-focused topics for the book. I’ll focus on two intersecting areas of research they’ve published recently: (a) the short- and long-term benefits of investing in children and (b) the upward mobility framework. I’ll first tackle investing in children.

Childhood poverty is a serious problem in the U.S. (about 16% of all children, or 11.4 million) and rarely receives the attention it deserves. Urban focuses specifically on the more than $500 billion the federal government invests in children (and their families) living in poverty annually. The investments include programs to reduce poverty in childcare, early education, health care coverage and nutrition (food subsidies), income, and housing. The investments are interconnected and can produce better outcomes when stacked together.

A report the Institute published this September says, “The payoff of any one investment can be difficult to assess because children benefit from a constellation of connected programs, and one investment can affect outcomes in many different domains. For example, investments in nutrition programs can reduce food insecurity, which in turn boosts health outcomes and leads to improved school performance. Doing better in school can lead to higher educational attainment, which is associated with better adult health because adults with higher education levels are more likely to have jobs with health benefits.”[1] (emphasis added)

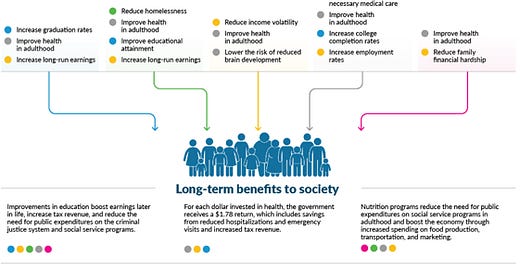

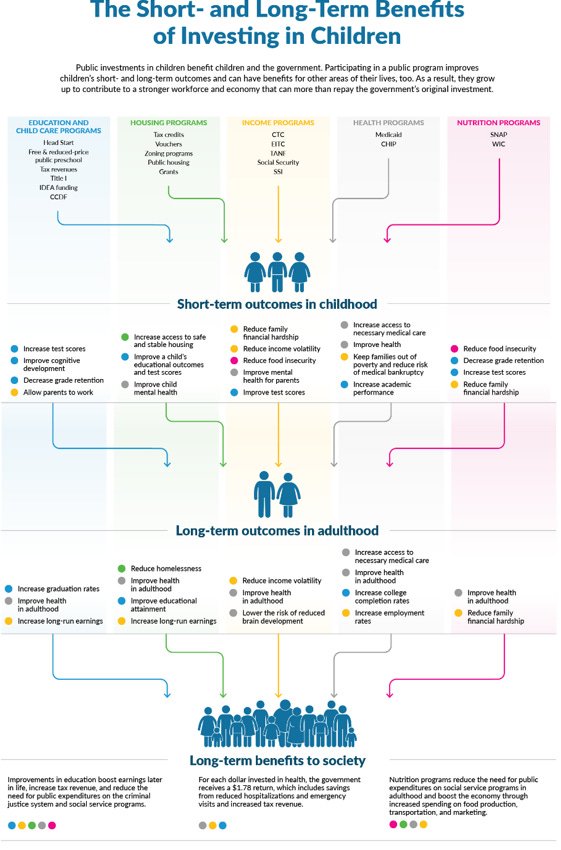

Urban has constructed a complex but elegant chart outlining the short- and long-term benefits of these investments. See below.

The chart shows the five investment domains with examples of the federal programs in each domain, such as Education and Childcare (Head Start and Title I), Housing (vouchers), Income (earned income tax credit), Health (Medicaid and CHIP), and Nutrition (SNAP & WIC). Investments in one domain can positively influence the outcomes in another domain.

Urban’s researchers indicate that, for example:

Children enrolled in Medicaid experience better health outcomes not only during childhood but into adulthood as well.

Nutrition and free meals programs decrease the likelihood of a child repeating a grade and increase test scores in Math and English.

Cash assistance through programs like the child tax credit and the earned income tax credit “improves mental health, reduces food insecurity, improves a child’s test scores, [and] reduces financial hardship,”[2] among other improvements.

Their findings on short-term outcomes go well beyond the above list.

As important, Urban’s researchers found impressive long-term outcomes through these investments. These outcomes include:

Access to federal nutrition programs leads to “better life expectancy outcomes and are more likely to be food secure in adulthood.”

Access to a range of these support programs shows an increase in high school and college completion rates.

Access to housing vouchers allows families to move to higher-opportunity (and lower-poverty) neighborhoods with better amenities and services, as well as attend higher-quality schools.

For every dollar the federal government invests in a child’s health, it receives a return of $1.78. Other investments “boost tax revenue and save money for the government by lowering spending on the criminal justice system and social service programs for adults.”[3]

Why are these investments crucial for leveling the playing field? Because African Americans, overall, live disproportionately in higher-poverty, lower-opportunity neighborhoods when compared with Whites, as we discovered in Myths 2 and 3, due to ongoing systems of racism and discrimination.

On average, because of these systems, their children are far more likely to attend high-poverty schools, their median household income is considerably lower than that of Whites, they experience greater health risks and lower life expectancies in significant part because of where they live, and they rent their housing at far higher rates than Whites, spending higher portions of their wages on housing (often 30-50%).

These federal investments matter and will continue to matter. And, just to be clear, they matter to Whites, too. More than 24 million live in poverty, by far the largest number of any race in the U.S.

Urban’s Upward Mobility Framework intersects directly with the research on federal investments in children. Its framework focuses on racial equity and establishes five “pillars of support” that residents need locally, and has a core focus on social and economic mobility. Mobility here refers to the ability to improve one’s status, often measured by one’s income.

Urban has established a three-part definition for upward mobility: economic success, that is, having sufficient income and assets to support them and their household; power and autonomy, meaning they can make important choices in – and have control over their lives; and dignity and belonging, referring to the respect and dignity they receive from contributing to family, work, and community.[4]

Once again, the think tank has created an elegant depiction of the framework, which you can see below. Racial equity is central to the framework since, as we’ve seen in previous posts, systemic racism remains firmly embedded in a wide range of policies, processes, institutions, and our national culture. Because systemic racism is found at each level of focus—local, state, and national—leaders at each level must ensure racial equity is embedded in their own policies and actions.

The five community-based pillars of support to guide paths to greater mobility are:

Rewarding work

High-quality education

Opportunity-rich and inclusive neighborhoods

Healthy environment and access to good health care

Responsive and just governance

The most obvious overlap between the federal investment framework and upward mobility comes with access to high-quality education and a healthy environment, most commonly found in high-opportunity neighborhoods. However, these neighborhoods must be inclusive, which historically they have never been. It is only in recent decades that more high-opportunity neighborhoods have become more accessible (but not without resistance) to African Americans and other people of color.

Raj Chetty from Harvard has been studying the science of economic opportunity for more than a decade. He argues that our nation should prioritize equality of opportunity but never has. He writes, “Opportunity is not equally distributed in America: People’s chances of achieving success vary widely depending upon their parents’ income, racial background, and ZIP code.”[5] (emphasis added)

He and his research team have looked at key data of hundreds of millions of Americans. In sum, their studies have shown that three elements must be true to have a genuine ‘opportunity economy’:

The roots of opportunity start at birth. Children who grow up in thriving environments (health and nutrition, education and housing, stable families, etc.) are far better prepared for success in adulthood.

Communities must be leveraged as the focus for change. Providing opportunities for families to move to better neighborhoods and investing in communities needing serious improvement can each make a significant difference.

The importance of social capital, i.e., where people with low incomes have friends with high incomes (and vice versa). Greater social capital, Chetty says, helps people make important life decisions, receive job referrals, get support in starting a business, etc.

Chetty articulates a range of policies that can make a difference, including housing vouchers, turning public housing projects into thriving mixed-income communities, improving teaching, counseling, and advising in K-12 schools, access to post-secondary programs that have been shown to increase economic mobility (not merely attending college), and providing successful targeted job training and workforce development programs.

His policy ideas coincide well with both of Urban’s frameworks.

The bottom line: We know a lot of what works and what matters. Yet our investments aren’t made cohesively. The support that should be in place instead is scattered and unintegrated locally. Over recent decades, racial equity has not been a central emphasis in hardly any of our policies, thus keeping a range of playing fields profoundly unequal.

If we are serious about creating level playing fields, more of us must advocate for these frameworks and the policies that logically flow from them.

[1] Anna Farr, Cary Lou, Hannah Sumiko Daly, and Display Date, “How Do Children and Society Benefit from Public Investments in Children?” Urban Institute, September 4, 2024, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-do-children-and-society-benefit-public-investments-children#:~:text=Investments%20in%20children%20act%20through,grow%20to%20their%20full%20potential.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Upward Mobility Framework,” Urban Institute, 2024, https://upward-mobility.urban.org/framework.

[5] Raj Chetty, “I Have Studied Social Mobility for Years. Here’s How Kamala Harris Can Build an ‘Opportunity Economy,’” New York Times, September 20, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/20/opinion/kamala-harris-opportunity-economy.html.