This is the first of a three-part series about Ferguson as a poster child for systemic racism and continued White domination. This part explores Ferguson's racial history and evolution from an all-White town to a majority-Black one.

You could choose just about any city in America and discover quickly how all eight myths from my book intermingle in very similar ways – from New York City in the Northeast to Atlanta in the Southeast to Chicago in the Midwest to Los Angeles out West. As America discovered during the pandemic, these fictions hold true in one of the whitest cities in America, Portland, Oregon—and in cities you may never have heard of, like Kenosha, Wisconsin (where police shot and paralyzed unarmed Jacob Blake man) or Aurora, Colorado (where police unnecessarily took down and injected a Black autistic man, Elijah McClain with ketamine, leading to his death).

Like most of America, I hadn’t heard of Ferguson, Missouri until August 2014. A White policeman’s murder of an unarmed Michael Brown put the town on the map. Although the protests that came in the aftermath were not the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement (George Zimmerman’s murder of Trayvon Martin was), they were an accelerant. The movement established its staying power in the aftermath of Michael’s murder. White America paid attention for a month or so, then moved on. Two separate times the policeman, Darren Wilson, was acquitted of any criminal wrongdoing. Given the enduring challenges around police immunity, there is no surprise there.

What I failed to explore further at the time were the underlying conditions that led up to Brown’s murder and the uprising afterward. It wasn’t until 2020 that the pandemic provided me the time to dive deeply into all these issues.

The history of Ferguson is, in many ways, a replica of the racial history of hundreds of communities in just about every state in the union. It’s a history that reinforces just about every dimension of systemic racism and the eight myths in my book, It’s Never Been a Level Playing Field … white flight, declining inner ring suburbs, segregated schools, poor health outcomes, environmental injustice, racist politics, and a community of Black residents who find it near impossible to build any wealth.

Ferguson, then, is a near-perfect illustration of how all these factors conspire to create a city designed to fail its African American residents.

Let’s first look at its local history and the racial history of the much St. Louis County.

Ferguson was founded in the late 19th century and remained a small town until a huge growth spurt after World War II, doubling its population to 22,000 residents in 1960. Ferguson, like many small towns in America, was an all-White town from its founding as well as a sundown town (partial list of sundown towns in the U.S.) until the 1960s. Thus, Black people were not allowed to stay in town after sunset, and if (or when) they did, they faced either White vigilantism or time in jail.

To understand Ferguson and its history, we must also understand the history of its neighbor to the west, Kinloch, a tiny, majority African American village. Early on, Kinloch’s population was larger and more diverse than Ferguson's until the late 1930s. That is when the white part of the town formed the new municipality of Berkeley after it lost an effort to split the town into two school districts, one White and one Black.[1]

At that point, Kinloch effectively became an all-Black town that held its own into the 1970s as a tight-knit community of shops, community centers, churches, and modest homes.

As you might imagine, the White city of Ferguson was not a friendly neighbor to Kinloch. For years, Ferguson mounted a physical barrier that blocked the main roadway to get into Ferguson from Kinloch.

In 1968, Ferguson’s White mayor surprisingly had the barrier removed. Shortly after, a White city councilman proposed erecting a 10-foot fence between the two communities, something he actively lobbied for well into the 1970s. This councilman argued that the fence would reduce vandalism and burglaries. Opponents dubbed it Ferguson’s ‘Berlin Wall.’[2] Even after a narrow Council majority defeated his plan, he then offered a plan enabling homeowners to leverage low-interest loans to build fences independently.

Meanwhile, during the last decades of the 20th century, Kinloch lost much of its population when St. Louis (the city, not the county) bought out many Kinloch homeowners at prices lower than the homes were valued so that the nearby international airport could add a runway.

Not surprisingly, this ‘negro removal’ (as James Baldwin called it) devastated the Kinloch economy and community. From 1970 to 2000, Kinloch’s population plummeted from more than 5,500 to less than 500. [3] Despite a noise-abatement agreement forged then, a long-promised redevelopment plan for the community is only now underway—40 years later.

As Kinloch was intentionally shrunk, many of its displaced Black residents moved to places like the worn-down Canfield Green apartment complex in Ferguson, where Michael Brown was killed.

Even though Kinloch shared a border with Ferguson, their schools stayed separate until a federal court ordered the Ferguson school district to annex the two adjacent school districts, Kinloch and Berkeley, in 1975 (21 years after Brown v. Board of Education) as part of a larger school desegregation effort.[4]

The entire Greater St. Louis region is one of the most segregated in the country.

The first Black family moved into Ferguson in 1968, buying a home and causing much consternation among their white neighbors, who did not want Blacks to move into Ferguson.

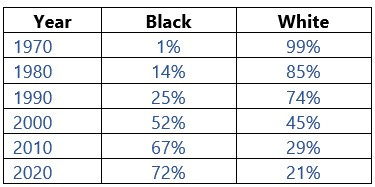

The racial demographics changed dramatically in the city from 1970 to 2010, with whites fleeing as Blacks moved in. The chart on this page shows the rapid demographic evolution of the town from majority-white to majority-Black.

In the aftermath of the Michael Brown murder in 2014, Ferguson’s population declined significantly (nearly 40%) from about 21,200 to 18,500, with Whites leaving in large numbers and even Blacks leaving in smaller numbers.

The out-migration of lower-income, most often Black residents from northern parts of the City of St. Louis helped instigate this sea change in Ferguson’s demographics. In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, an incredible outflow of manufacturing jobs out of St. Louis—as occurred in so many midwestern, industrial cities—drove out many Black residents in their attempt to follow the job opportunities that, more broadly, were relocating from the city to the outer suburbs.[5]

A single statistic helps us understand the magnitude of the economic, geographic, and ultimately racial transformation: from 1951 to 1967, while jobs in St. Louis (where the majority of Blacks lived) dropped by 20%, employment in St. Louis County (where the majority of Whites lived) increased by 400%.[6]

When St. Louis razed its long-time failed Pruitt-Igoe housing project in northern St. Louis in 1972 (33 towers built on nearly 60 acres after World War II), many of the Black families who had lived there for up to 20 years had few places to migrate to other than the adjoining or nearby suburbs but as often, in other sections of the city’s White-created ghetto.

Even though housing project residents received a modicum of relocation assistance, many of the suburbs were off-limits for them to move to. Newer, all-white suburbs in St. Louis County ensured their zoning laws banned high-density housing (i.e., affordable apartment buildings), leaving Black residents with lower incomes and lower wealth with very limited suburban choices.[7]

Many of St. Louis’ Black residents attempted to work for firms like defense contractor McDonnell Douglas, which had established a significant suburban presence in St. Louis suburbs. Because of standard, racist real estate practices still in play in the 1960s in St. Louis County:

“the company maintained separate housing lists for white and black recruits so that employees of each race could be referred to their respective segregated communities. …

By 1970 the company employed nearly 3,000 nonwhite workers. The previous year alone, some 650 new hires at the plant were nonwhite. Yet when these employees, with good and stable jobs, sought housing, real estate agents still routinely referred them to the black Kinloch suburb, avoiding the many available homes in working-class white suburban communities nearer the plant. … real estate agents steered African American workers away from lower-middle-class suburbs.

Often these workers could find housing only far away in the St. Louis ghetto, resulting in long commutes and excessive absenteeism when carpooling arrangements failed. With public transportation, the commute took as much as two hours each way. Black workers at other industrial plants, increasingly located in the suburbs, faced similar challenges.”[8]This pattern largely repeated with the Chrysler assembly plant in Fenton, another St. Louis suburb. Black workers in the plant could not live in or near Fenton and thus had an hour or more commute to the plant. Even though Chrysler had a targeted recruiting and training program for Black workers, this program only had a 40% retention rate, primarily because of the transportation challenges Blacks faced. The plant opened in Fenton in 1959. To this day, the town is 96% white and one-half of 1% Black.[9]

In places like Ferguson—where Blacks legally could move to—the exodus of Blacks to the suburbs created tensions with white power brokers, who, according to former Missouri State Senator Jeffrey Smith, were accustomed to unquestioned decision-making around policing, and doling out construction and service contracts throughout their White networks.

Thus, St. Louis County employed the same racist practices as every other U.S. city and metro region: intentionally preventing Blacks from moving into White suburbs, forcing Blacks to either stay in the declining inner city or move to majority Black suburbs also on the decline, and causing these workers to either endure enormously long, public transit based commutes or lose their jobs entirely. This nationwide phenomenon caused severe economic and social deterioration in the African American community from the 1960s into the 1990s.

In many of these places, these white political and economic brokers protected and defended their status, leaving Blacks almost entirely out of any decision-making circles.[10]

“Majority-black Ferguson has a virtually all-white power structure: a white mayor; a school board with six white members and one Hispanic, which recently suspended a highly regarded young black superintendent who then resigned; a City Council with just one black member; and a 6 percent black police force. … ” Many North County towns — and inner-ring suburbs nationally — resemble Ferguson. Longtime white residents have consolidated power, continuing to dominate the City Councils and school boards despite sweeping demographic change. They have retained control of patronage jobs and municipal contracts awarded to allies. The North County Labor Club, whose overwhelmingly white constituent unions (plumbers, pipe fitters, electrical workers, sprinkler fitters) have benefited from these arrangements, operates a potent voter-turnout operation that backs white candidates over black upstarts. The more municipal contracts an organization receives, the more generously it can fund re-election campaigns. Construction, waste, and other long-term contracts with private firms have traditionally excluded blacks from the ownership side and, usually, the work force as well.[11]

This passage is a painful articulation of Myth 1 in my book, America Provides an Equal Playing Field for All, when in reality, Whites still hold almost all the levers of power, especially, but by no means limited to, places like Ferguson.

It is important to recognize that because of the local protests organized by local organizations and supported by the national Black Lives Matter movement, important changes have occurred in the past 10 years. For example, because of tireless organizing by African Americans and the civic organizations they represent, Ferguson now has:

Its first Black Mayor

Its first Black police chief

A police force that is about 50% African American

Police officers required to wear body-cameras

Also, a mediator during the uprising—an African American lawyer from Ferguson—became the first Black St. Louis County prosecutor.

Undoubtedly, this is important progress, but what happened as a result of the vocal advocacy for racial justice in the U.S. after the uprisings in Ferguson remained very local. Just like the uprisings that occurred after George Floyd’s murder resulted in little progress on police reform in Minnesota or elsewhere. nationally, except in a few pockets.

Ferguson still has a very long way to go to achieve any semblance of a level playing field.

In my next post, I’ll look at economic, educational, and health inequality. In the last in the series, later this week, I’ll focus on the local justice system. As a Ferguson resident said in a St. Louis Public Radio article this past summer commemorating the 10th anniversary of Michael Brown’s death:

“Justice is a living, breathing Michael Brown … Accountability would have been the officer that killed him being tried.”[12]

Footnotes

[1] Jeffrey Smith, “You Can't Understand Ferguson Without First Understanding These Three Things,” The New Republic, August 15, 2014, https://newrepublic.com/article/119106/ferguson-missouris-complicated-history-poverty-and-racial-tension.

[2] Mary Delach Leonard, “Ferguson's yesterdays offer clues to the troubled city of today,” St. Louis Public Radio, August 2, 2015, https://news.stlpublicradio.org/government-politics-issues/2015-08-02/fergusons-yesterdays-offer-clues-to-the-troubled-city-of-today.

[3] Joseph Goldkamp, “It’s Complicated: Ferguson, Local Activists, and the Missouri History Society Negotiate Accession of Artifacts,” Nonprofit Quarterly, September 29, 2016, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/complicated-ferguson-local-activists-missouri-history-society-negotiate-accession-artifacts/.

[4] “Ferguson-Florissant School District,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferguson-Florissant_School_District.

[5] Denver Nicks, “How Ferguson Went From Middle Class to Poor in a Generation,” TIME, August 18, 2014, https://time.com/3138176/ferguson-demographic-change/.

[6] Richard Rothstein, "The Making of Ferguson," Economic Policy Institute, October 15, 2014.

[7] Denver Nicks, “How Ferguson Went From Middle Class to Poor in a Generation,” TIME, August 18, 2014, https://time.com/3138176/ferguson-demographic-change/.

[8] Richard Rothstein, "The Making of Ferguson," Economic Policy Institute, October 15, 2014.

[9] Richard Rothstein, "The Making of Ferguson," Economic Policy Institute, October 15, 2014.

[10] Jeffrey Smith, “You Can't Understand Ferguson Without First Understanding These Three Things: Reflections from a former state senator from St. Louis,” The New Republic, August 15, 2014, https://newrepublic.com/article/119106/ferguson-missouris-complicated-history-poverty-and-racial-tension.

[11] Jeff Smith, “In Ferguson, Black Town, White Power,” The New York Times, August 17, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/18/opinion/in-ferguson-black-town-white-power.html.

[12] Madison Holcomb, “A decade after Michael Brown’s death, people in Ferguson see change and more work ahead,” St. Louis Public Radio, August 8, 2024, https://www.stlpr.org/culture-history/2024/08-08/feguson-panel-reflects-10-hyears-michael-brown-jr-death.

I appreciate the historical background as a context for what happened to Michael Brown. In view of Trump's recent election, it's clear that we have a very long way to go. On another note, you make the statement that "Ferguson’s population declined significantly (nearly 40%) from about 21,200 to 18,500". As a math teacher I have to point out that the decline is a little less than 13%, not 40%. This doesn't diminish the impact of such an exodus.