Ignore Tr*mp: Here are the Transformative Federal Investments We Need for Black Entrepreneurs

“It was never the case that a white asset-based middle class simply emerged. Rather, it was government policy, and to some extent literal government giveaways, that provided whites the finance, education, land, and infrastructure to accumulate and pass down wealth.”[1]

Darrick Hamilton and Trevon LoganBottom Line Upfront: BLUF

1. America’s Original Affirmative Action – For over two centuries, federal policies—from slavery to the Homestead Acts to redlining to the GI Bill—systematically advantaged White Americans with wealth-building tools while excluding Black Americans from similar opportunities.

2. Affirmative Action’s Irony – While meant to address historic exclusion, modern affirmative action has been vilified as providing unearned benefits to Black Americans, even though White women are its main beneficiaries.

3. Persistent Business Ownership Gap – Although African Americans comprise 13% of the U.S. population, they own only 4% of businesses, a disparity driven by more than a century of unequal access to capital.

4. Capital Disadvantage – White households’ median wealth is nearly 10× higher than Black households’, giving White entrepreneurs a decisive startup advantage in funding from personal savings and family networks.

5. Loan Inequities – Black business owners face more than double the loan denial rates of White owners and receive significantly smaller, costlier, and less favorable financing—even when they demonstrate stronger financial profiles.

6. Remarkable Resilience – Despite systemic barriers, Black entrepreneurship has surged—especially among women—with Black-owned firms growing 34% from 2012–2021 and contributing $207B to the economy.

7. Wealth Multiplier Effect – Black business ownership is a powerful wealth-building tool, with median net worth for Black entrepreneurs 12× higher than Black nonbusiness owners.

8. Federal Action Imperative – Centuries of exclusion demand transformative investment, including scaling Minority Business Development Agency centers, boosting CDFI funding to $2B, and tripling microenterprise programs.

9. Catalysts for Growth – Other proven strategies include minority business accelerators, targeted tax credits for investors, expanded procurement opportunities, and permanent expansion of the New Markets Tax Credit.

10. A Historic Opportunity – With sustained, large-scale federal investment, the U.S. can finally shift from a legacy of exclusion to one of equitable economic empowerment for Black entrepreneurs.

Intro: The Full Extent of White Advantage for Almost Our Entire Economic History

Our American economic system has long been one where capitalist structures are shaped by racial hierarchies, with Whites always on top, and Blacks throughout nearly our entire history at the bottom. This system has led to different treatment and valuation of people based on race, with Blacks exploited and Whites gaining an ongoing advantage, especially in accumulating capital. The advantages and exploitation mutually reinforce each other.

When policies are designed to advantage a race perpetually, we can look at it as a form of affirmative action. Our nation has always taken affirmative action to ensure results, benefits, and advantages are conferred to Whites.

Our society and our economic system have been intentionally designed to take affirmative action on behalf of White people to benefit White people from the beginning: from the most egregious (slavery) to the more mundane (the U.S. tax code) and nearly everything in between.

This broader affirmative action for White people has determined who receives land (the Homestead Acts), who can benefit from job programs (the New Deal), who is rewarded for service to their country (the GI Bill), and who can easily access capital for higher education and starting a business.

Now obviously this is not how the term affirmative action has been used or defined since the federal government instituted it in the early 1960s, in which special consideration was granted to “groups considered or classified as historically excluded, specifically racial minorities and women.”[2]

Why did President Kennedy issue his executive order for affirmative action?

To finally and intentionally enable Blacks to benefit more from our economic system. Specifically, to try to level the playing field in hiring within the federal government and in college admissions.

Although Whites have benefited from broad forms of affirmative action and ongoing advantages from 1776 through today, many White people have actively opposed affirmative action policies from their very beginning (1962) and have worked to overturn them at nearly every opportunity.

Almost immediately, opponents made affirmative action a pejorative term that accuses Black people of receiving, ostensibly, economic benefits they don’t deserve. Ironically, the largest recipients of affirmative action policies since the early 1960s have not been African Americans but White women. Also, ironically, in the twenty-first century, a majority of White women now oppose the continuation of affirmative action.

In this newsletter, I discuss how our policies to address the historical exclusion and discrimination of African Americans have fallen well short of creating a system that enables African Americans to benefit equitably from our economy.

In particular, I want to show how much it has fallen short in supporting Black entrepreneurs and business owners compared to White entrepreneurs and business owners.

Lack of Access to Capital for Black Entrepreneurs

Many factors have contributed to—and still contribute to—the racial wealth gap between Whites and Blacks. I’ve discussed many of these in previous newsletters. Since America’s beginning, Whites have consistently had significant economic advantages that Blacks rarely experienced, many of which help build wealth through better education, jobs, and homeownership access.

So, just as there’s always been a racial wealth gap and racial homeownership gap since time immemorial, there’s also been a business ownership gap. Even though African Americans comprise nearly 13 percent of the U.S. population, they account for just over 4 percent of its 22.2 million business owners.

How has this gap been sustained?

To state the obvious, access to capital for small businesses is a critical economic issue in the United States today. Small businesses play a major role in job creation, contributing 50-70% of new jobs annually, and in economic growth, accounting for 40-50% of economic activity. As a nation, we must ensure that “entrepreneurs and creditworthy firms can secure adequate financial resources for growth and success." Ensuring that these firms have sufficient access to financial capital allows them to continue driving innovation, growth, and job creation in the U.S. economy.[3]

Typically, entrepreneurs depend on personal savings, with as many as 20 percent relying on family for funding. White households’ median wealth is nearly ten times greater than that of Black households, which puts new Black entrepreneurs at a clear disadvantage when starting businesses because “access to initial capital strongly impacts a firm’s chance of success.”[4]

Although the number of businesses owned by people of color has grown significantly over the past decade, small White-owned companies generate more than twice the average sales compared to small Black-owned businesses. African American–owned enterprises also face higher failure rates, often because their companies are “overrepresented in less successful industries (for example, in the personal services industry), as well as entrepreneurs of color start their businesses with less capital than their white counterparts.”[5]

Entrepreneurship is especially difficult for Blacks compared to Whites, who have significantly higher rates of college degrees than Blacks. Entrepreneurs with a college degree are more likely than those with only a high school diploma to generate (1) sales exceeding $100K and (2) employ more paid staff. Many Black entrepreneurs start at this disadvantage and face additional struggles from there.

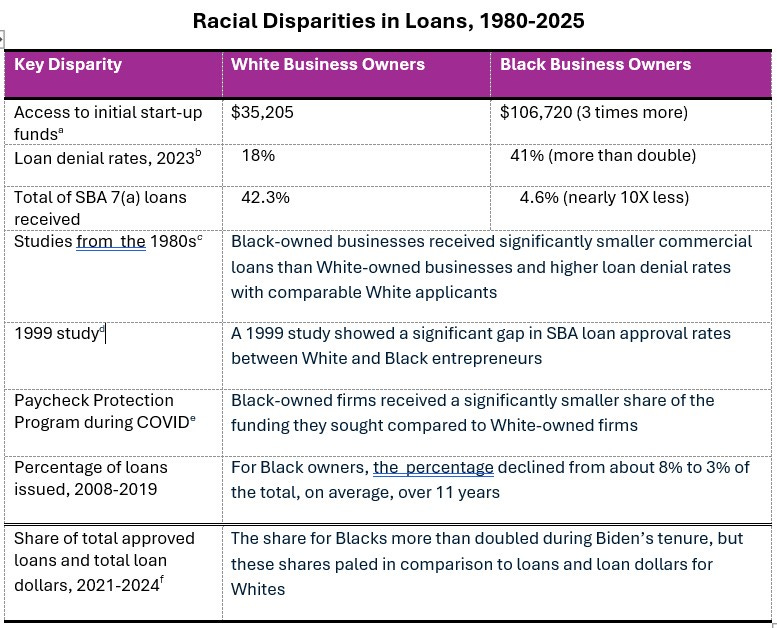

Review the table below and observe the disparities between White and Black business owners that have persisted throughout the history of the Small Business Administration.

These disparities are shameful. Yet, it’s actually worse than the data you see above:

From 2020 to 2024, Black business owners with stronger financial profiles than White entrepreneurs still faced higher rejection rates. [6]

A 2022 study showed “Black business owners who concealed their race in loan applications obtained 52% more in funding than Black business owners who reported their race.”[7]

That same study found that Black business owners with stronger financial profiles than White owners were offered less desirable and more expensive options (with higher fees and rates) than White owners.[8]

Finally, in a different study conducted by 12 Federal Reserve Banks, with Black, White, and Latino-owned firms applying for financing and presenting a low credit risk, “low-credit risk businesses with Black and Latino owners were approved for full financing at nearly the same rate as high/medium credit risk white-owned firms.[9]

Yet Black Entrepreneurs Persist

Chronic disadvantages have not prevented Black people from starting businesses, especially Black women. African American women-owned firms make up 61 percent of all African American–owned firms. From 2007 to 2016, the number of African American women-owned firms grew by 112 percent—more than doubling—and far surpassed the overall 45 percent increase among all women-owned firms.[10]

Black entrepreneurship is important for many reasons, especially for building wealth.

“[T]he median net worth for Black business owners is 12 times higher than Black nonbusiness owners. Further, it is not because they started out wealthier. . . . [B]usiness owners grew their wealth more and grew it faster. Starting a sustainable and healthy business is a viable and critical pathway to breaking the cycle of low wealth.”[11]

Starting a business in America is a crucial step to building wealth. However, only 6 percent of Black business owners get their main credit from banks, which is four times less than the average for all credit-seekers. When Black business owners do receive credit—which they often don't—they typically get 57 percent less than White owners. Additionally, only 1 percent of Black small businesses manage to secure a Small Business Administration loan.[12]

Yet, there are very heartening statistics to consider as well.

Black-owned businesses provide over 1.3 million W-2 jobs and 90% of Black owners employ at least one worker.

Black-owned businesses contribute more than $207 billion to the national economy. Annual revenues from these businesses grew by more than 43% between 2012 and 2021.

The number of Black-owned businesses increased by 34% in that same time period, outpacing overall business growth, which was 19%.

Employees of Black-owned businesses grew by 33% from 2012 to 2021.[13]

Thus, despite poorer access to startup capital and despite severe loan denial rates, African American businesses have continued to grow impressively in the past decade and a half.

Due to systematic exclusion and discrimination in the capital lending market, I believe the federal government has a special obligation to make clear and substantial investments in Black businesses at an unprecedented level.

Obviously, it’s extraordinarily unlikely that any of this will occur during the 2nd Tr*mp administration, but we should remain ready for whenever the next windows of opportunity open up.

A Potential Line-up of Future Federal Investments in Black Businesses

Numerous think tanks and thought leaders heavily informed my thinking about what we should make possible.

The Brookings Institution proposes a new Minority Business Accelerator grant program to support accelerators that focus on new and existing entrepreneurs of color. The core focus of these accelerators would be to invest in minority businesses already attaining $1 million in revenues per year to help them scale in revenues, productivity, and staff size with an emphasis on what is known as business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-government (B2G) firms. Each local or regional accelerator would look to align its supply chain strategies to the unique needs of the local minority business ecosystem.

Accelerators would also pave the path to operating capital for businesses to assist with this growth. Cincinnati’s Minority Business Accelerator is viewed as a model for what could happen. The portfolio of businesses it has supported in recent years (sixty-seven in total) has led to significant job creation (more than 3,500 jobs) and major expansions in revenue of those businesses (now $1.5 billion in aggregate).[14]

The Center for Global Policy Solutions think tank proposes a robust range of federal policy solutions to increase the number of successful Black entrepreneurs, including:

Dramatically increasing the number of Minority Business Development Agency business centers (part of the Small Business Administration [SBA]) and the outreach they conduct;

Expanding access to entrepreneurship training in both K–12 education curricula and in postsecondary, career, and technical education; and

Providing a tax credit for venture capitalists who invest in Black entrepreneurs and Black-owned small businesses.[15]

The Local Initiative Support Corporation, mentioned above, strongly recommends increasing the U.S. Treasury Department’s CDFI Fund budget to $2 billion (up from $331 million in 2023) to enable CDFIs to expand and meet the needs of local entrepreneurs.

The focus here should be on entrepreneurs of color, especially (but not exclusively) in redevelopment projects within federally designated Opportunity Zones, Promise Zones, and Choice Neighborhoods. These funds could be increased if the U.S. Treasury Department established a CDFI direct-loan program that provides CDFIs with capital for loans outside of the Treasury’s annual Fund award process.

Congress should also create a tax credit supporting direct investment of both equity and grants into CDFIs to help them increase lending in chronically disinvested communities, from microloans to smaller start-ups through to larger loans for businesses primed to grow.[16]

Further, the federal government should triple the funding in the Program for Investment in Microentrepreneurs (PRIME). This would allow for more financing for lower-income entrepreneurs and for entrepreneurs employing five or fewer staff.

LISC advocates for passing “The Unlocking Opportunities in Emerging Markets Act to establish an Office of Emerging Markets (OEM) within SBA’s Office of Capital Access. The office would “ensure that SBA’s access-to-capital initiatives address the needs of entrepreneurs in underserved markets, precisely and comprehensively . . . and the Minority Business Resiliency Act . . . to ensure minority entrepreneurs across the nation are equipped with the resources and tools needed to grow.”[17]

We also need to not only make permanent the New Markets Tax Credit Program but also to increase its funding fivefold to provide credits for equity investment in small businesses that benefit low- and moderate-income areas. Since its inception in 2003, this tax credit program has created or retained more than eight hundred thousand jobs and provides highly favorable terms to small businesses that cannot get those terms elsewhere. Most impressively, every dollar the government invests in this program generates more than $8 from the private sector.[18]

The federal government should also equalize federal and state procurement processes by significantly expanding the contracting opportunities and technical assistance that small, disadvantaged businesses can access.[19]

Finally, the Center for American Progress recommends ways to revamp the focus of the Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA):

Make competitive grants to HBCUs and other minority-serving institutions (MSIs) to run incubators and accelerators for minority-owned businesses, including grant funding to invest capital in budding BIPOC entrepreneurs and featuring free back-office services (HR, IT, legal, accounting, etc.) with initial funds of $1 billion.[20]

Launch a minority business investment company (MBIC) program to lend low-cost, government-backed investment funds to a private, licensed equity fund management firm to use the loan and its own capital to make debt and equity investments in Black-owned businesses and other businesses of color. The firm would “have to pay the MBDA a licensing fee and invest 100 percent of total capital in certified minority-owned businesses . . . and create a dedicated stream of capital and expert guidance for entrepreneurs of color who have long been excluded from mainstream investment systems.”[21]

Over more than two and a half centuries, our nation has intentionally neglected and ignored vital investments in Black neighborhoods, Black businesses, and Black entrepreneurship. The long-overdue investments proposed here will finally begin to correct that history.

Footnotes

[1]. “The Racial Wealth Gap: Understanding the Economic Basis for Repair,” Reparations4Slavery, https://reparations4slavery.com/the-racial-wealth-gap-understanding-the-economic-basis-for-repair/.

[2] “Affirmative Action in the United States,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affirmative_action_in_the_United_States.

[3] Alicia Robb, “Financing Patterns and Credit Market Experiences: A Comparison by Race and Ethnicity for U.S. Employer Firms,” Office of Advocacy, U.S. Small Business Administration, February 2018, p. 3.

[4]. Ewing Marian Kauffman Foundation, “Including People of Color in the Promise of Entrepreneurship,” Entrepreneurship Policy Digest, December 5, 2016, p. 1, https://www.kauffman.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Including-People-of-Color-in-the-Promise-of-Entrepreneurship-PDF.pdf.

[5]. Ibid, p. 2.

[6] “SBA Data Show Major Increase in Loans to Black-Owned Businesses under Biden-Harris,” U.S. Small Business Administration, September 21, 2023, https://www.sba.gov/article/2023/09/21/sba-data-show-major-increase-loans-black-owned-businesses-under-biden-harris.

[7] Kacie Goff, “Study: Racial biases continue to impact loan approvals for minority business owners,” Bankrate, July 5, 2025, https://www.bankrate.com/loans/small-business/racial biases-impact-loan-approval-for-minority-business-owners/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Credit Survey Finds White-Owned Small Businesses Were Twice as Likely to be Fully Approved for Financing as Black-and Latino- Owned Firms,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, April 15, 2021, https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/news/regional_outreach/2021/202104415.

[10]. “The State of Women-Owned Businesses Report: A Summary of Important Trends, 2007–2016,” American Express OPEN, April 2016, p. 5, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53ee2f53e4b08ae50e0b57a4/t/574f0fd64d088e84c52496de/1464799202454/2016SWOB.pdf.

[11]. “The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America: Untapped Opportunities for Success,” Association for Enterprise Opportunity, p. 4, https://aeoworks.org/images/uploads/fact_sheets/AEO_Black_Owned_Business_Report_02_16_17_FOR_WEB.pdf

[12]. Ibid, pp. 24–25.

[13] “Black Business Ownership Fact Sheet,” Association for Enterprise Opportunity, 2024, https://epop.norc.org/content/dam/epop/media/in-the-news/pdf/2025-black-business-ownership-fact-sheet.pdf.

[14]. Joseph Parilla and Darrin Redus, “How a new Minority Business Accelerator grant program can close the racial entrepreneurship gap,” The Brookings Institution, December 9, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-a-new-minority-business-accelerator-grant-program-can-close-the-racial-entrepreneurship-gap/.

[15]. Algernon Austin, “The Color of Entrepreneurship: Why the Racial Gap among Firms Costs the U.S. Billions,” Center for Global Policy Solutions, pp. 20–22, http://globalpolicysolutions.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Color-of-Entrepreneurship-report-final.pdf.

[16]. “LISC Policy Priorities for Economic Development, Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), https://www.lisc.org/media/filer_public/e1/07/e1072436-1092-4b42-8a6d-5637dba7a7d7/102720_lisc_policy_priorities_economic_development.pdf.

[17]. Ibid.

[18]. “Fact Sheet: Community Revitalization by Rewarding Private Investment,” Treasury Department -New Markets Tax Credit Program-CDFI Fund, September 2020, https://www.cdfifund.gov/Documents/NMTC%20Fact%20Sheet%20English%2016SEPT2020%20FINAL.pdf.

[19]. “Lift Every Voice: The Biden Plan for Black America, Biden-Harris Campaign, 2020, https://joebiden.com/blackamerica/.

[20]. Maxwell et al., “A Blueprint for Revamping the Minority Business Development Agency,” Center for American Progress, July 31, 2020, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2020/07/31/488423/blueprint-revamping-minority-business-development-agency/.

[21]. Ibid.

Footnotes from the Table

a. JaNay Queen Nazaire, “How Investors and Business Owners Can Create an Equitable Recovery for Cities—Hint: It starts with being actively anti-racist,” U.S. News & World Report, July 17, 2020, https://www.usnews.com/news/cities/articles/2020-07-17/how-anti-racist-policies-can-create-an-equitable-recovery-for-cities.

b. Ibid.

c. Timothy Bates, “Available Evidence Indicates that Black-Owned Firms Are Often Denied Equal Access to Credit,” a section to a report to the Federal Reserve, “Access to Credit for Minority-Owned Businesses, 1991.

d. Ken Cavalluzzo, Linda Cavalluzzo, John Wolken, “Competition, Small Business Financing, and Discrimination: Evidence From a New Survey,” Georgetown University / Center for Naval Analyses, February 1999, https://www.federalreserve.gov/Pubs/feds/1999/199925/199925pap.pdf.

e. Howell et al, “Racial Disparities in Paycheck Protection Program Lending, National Bureau of Economic Research, December 1, 2021, https://www.nber.org/digest/202112/racial-disparities-paycheck-protection-program-lending.

f. Kacie Goff, “SBA loan statistics: Race and gender,” November 22, 2023, Bankrate, https://www.bankrate.com/loans/small-business/sba-loan-race-and-gender-statistics.