And Yet, There’s Still Progress on Racial Equity and Justice

“Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Bottom Line Upfront

Community Ownership as Wealth-Building: In a powerful model of economic self-determination, Chicago TREND facilitated the purchase of a local strip mall by 52 small-dollar investors—many of whom are Black residents—creating shared ownership and revitalizing a long-neglected commercial space in a historically disinvested neighborhood.

Democratizing Commercial Real Estate Access: Chicago TREND’s “Buy Back the Block” playbook offers a blueprint for inclusive ownership in commercial real estate. It aims to disrupt the current situation in which 1% of U.S. households own 81% of commercial property and provides Black communities with tools for long-term wealth creation and financial equity.

Data-Driven Equity: The Black Progress Index: A collaboration between Brookings and the NAACP, this national index identifies key predictors of Black well-being across counties—enabling local leaders to target the structural causes of inequality and learn from high-performing regions, with an emphasis on evidence-based progress.

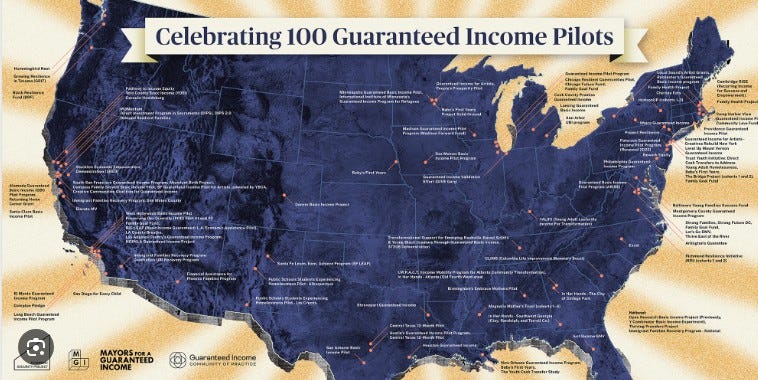

Guaranteed Basic Income as an Equalizer: With strong evidence from pilot programs in cities like Stockton, CA, guaranteed basic income (GBI) is emerging as a transformative policy that reduces income volatility, improves mental health, and enhances self-determination for low-income individuals, including those in Black communities historically excluded from economic security.

Black Architects Rebuilding Altadena: After devastating wildfires in a historically Black neighborhood of L.A., a coalition led by Black architects mobilized to preserve cultural legacy, prevent gentrification, and protect Black generational wealth through equitable, community-led reconstruction—a model of resilience and ownership in disaster recovery.

A Bipartisan Boost for Affordable Housing: The Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act of 2025, supported by over 100 bipartisan sponsors, represents a rare instance of political unity to tackle America’s housing crisis by expanding the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit—offering hope for increasing the supply of affordable housing across diverse communities.

Justice Reform Through Debt Forgiveness and Expungement: Dauphin County, PA, has eliminated $60 million in jail debt, and Maryland’s new Expungement Reform Act expands opportunities for people—disproportionately Black—to clear their criminal records, promoting reintegration and challenging punitive economic traps within the justice system.

Higher Education Resistance to DEI Attacks: Rutgers University faculty launched a solidarity compact across the Big Ten and beyond to resist political attacks on DEI and academic freedom collectively. Courts have begun to block Trump’s attempts to strip school funding over DEI, signaling a critical legal check on executive overreach.

#racialequity, #racialjustice, #communityownership, #GBI, #UBI, #Altadena

My focus this week is on heartening news. Despite the attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion, and the executive orders likely to disproportionately impact African Americans, important good news can still be found in many interesting places.

Read on!

Enabling Community Ownership in Strip Mall Revitalization

Lyneir Richardson, CEO of a real estate development company in Chicago, is a colleague I met through my work a couple of years ago with the Small Business Anti-Displacement Network (SBAN). Recently, Lyneir published a case study report that reviews his company's process for revitalizing a shopping center in a Black neighborhood in Chicago, which enabled local, community-based ownership of the property—rather than ownership by a national real estate corporation—to help ensure long-term community benefits.

The $6 million transaction for a 27,000 square foot strip mall and an adjacent parcel included “52 small-dollar investors, many of whom are local residents, reflecting a model of shared community ownership that fosters wealth-building in a historically disinvested neighborhood.”

Read more HERE.

The racial wealth gap in the U.S. is 8:1 between Whites and African Americans. This disparity has persisted since the 1960s due to various forms of subtle and overt economic discrimination and exclusion.

Increasing opportunities to build wealth in African American neighborhoods are essential; beyond increasing home ownership, which has a vast White-Black disparity (as of 2022, 75% vs. 45%), strategies like those pursued by Chicago TREND are key. Too many majority-Black neighborhoods are filled with declining strip malls owned by individuals and companies that do not live there and have no vested interest in their improvement.

Buying Back the Block: Democratizing Commercial Real Estate Ownership

The racial wealth disparity is also why Lyneir recently published “A Playbook to Buy Back the Block: How Community Practitioners Can Foster Inclusive Ownership of Commercial Real Estate” (Click HERE) as a guide to democratize access to commercial real estate ownership.

Why democratize?

Because he states that 1% of U.S. households own 81% of the dollar value of commercial real estate (CRE), his company, Chicago TREND, is one of a small but growing group of Black-owned real estate companies aiming to discover commercial real estate opportunities that residents and business owners can collectively own to increase Black wealth.

Lyneir writes:

“This playbook is designed to be a valuable resource for individuals with limited experience in the buying and selling of CRE. It aims to assist more people of color in acquiring CRE properties that provide annual cash flow and offer specific income tax benefits and the potential for long-term appreciation in value, which can be realized upon refinancing or selling the property.”[1]

A National Black Progress Index: an NAACP & Brookings Institution Partnership

I came across this index for the first time this week, although the article I read[2] was from 2022.

The Brookings Institution and the NAACP compiled data from hundreds of counties across the nation to “identify the strongest predictors of well-being” for Black communities, examining key drivers that political leaders, from national to local, can use to track progress while also identifying structural causes where progress has been slow or regressive.

In other words, if we’re to make more persistent progress in African American communities (most of which remain highly segregated), we need to understand what factors really matter, those that facilitate and those that impede progress.

The article appeared in a relatively new Black media source, The Emancipator (https://theemancipator.org), which publishes critical articles on race in America every week, primarily focusing on African Americans. Launched at Boston University in 2021 by Ibram Kendi, starting this year, The Emancipator will be published from the nation’s oldest historically Black university, Howard University, in Washington, D.C.

In the introduction the Index, the lead researchers write: “A goal of this research is to identify which social factors are the most important, provide evidence on the size of their effects, and track the places that do better or worse on these factors, as well as the places that over- or under-perform relative to predictions. There may be valuable lessons from the people and organizations in places that have better outcomes than expected.”

What were the top-performing counties in 2022?

They “include Cumberland County in the Portland, Maine metro area; Loudon, Fairfax, Prince William, and Montgomery counties, all outside of Washington, D.C.; Collier County in the Naples, Fla. metro area; Rockingham County, N.H., outside of Boston, and Snohomish County, Wash., near Seattle.”[3]The Impact of Guaranteed Basic Income on Income Inequality in the U.S.

In the mid-1960s, Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed:

“The solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.”

I briefly referenced Guaranteed Basic Income (GBI) in two previous newsletters. Through a city or county government, GBI provides citizens with cash transfers to help cover some of their basic expenses. It is deployed as a monthly recurring payment in pilot communities, often lasting for 1-2 years. The monthly amount can range from $500 to $1,000.

GBI “is intended to create an income floor below which no one can fall. … Guaranteed income typically focuses on specific individuals within a community, ensuring that those with the greatest need are prioritized for assistance.”[4]

You can’t even begin to build wealth if you can’t escape poverty. GBI is one way, regardless of race, to help people climb out.

Some advocates view guaranteed basic income as a strategy to reduce income inequality in the U.S. if implemented nationally. How significant is that inequality nationally, and why is addressing it so important?

In 2019, the top one percent of U.S. households earned 29 times (approximately $2 million) the median household income (about $69,000). UBI is provided regardless of employment status, and there are no restrictions on how the money can be spent.Nearly 250 cities and counties are now a part of a national coalition (Mayors for GBI Link. and its partner coalition, Counties for GBI. Link) with dozens of jurisdictions having implemented pilot initiatives over the past five years, including two of the largest counties in the U.S. (Cook County, IL, home to Chicago, and Los Angeles County, CA).

A research team from the University of Tennessee and the University of Pennsylvania found that in Stockton, CA, Economic Empowerment Demonstrated (the first known GBI initiative in the country), individuals’ participation in the program after one year was associated with:

Reduced income volatility

Increased full-time employment

Improved health and well-being

Reduced depression and anxiety

Diminished feelings of financial scarcity and new opportunities for self-determination, choice, goal-setting, and risk-taking[5]

It is rare to see such achievements in anti-poverty initiatives within the span of a year. More recent research in other jurisdictions has found similar results.

Guaranteed Basic Income is a strategy I highlight in the “Transforming Pathways to Economic Prosperity” chapter in my book, It’s Never Been a Level Playing Field: Overcoming 8 Racial Myths to Even the Field.

However, we also know that in this political climate, supporting those who are less fortunate means GBI efforts are likely to become harder to achieve and sustain, especially as they become more visible.

Black Architects Rebuilding Altadena After the L.A. Wildfires

The Eaton Fire in Los Angeles destroyed 9,400 buildings and homes in January in Altadena, a historically Black community in the L.A. area that is now home to residents of many races.

In the aftermath, a coalition of Black architects, engineers, contractors, and other construction professionals (the Altadena Rebuild Coalition) quickly joined forces to ensure:

(1) cultural preservation and historical significance

(2) community engagement in the rebuilding, and

(3) rebuilding support.

The fire destroyed nearly half of all Black homes in the community, compared to just over a third of homes belonging to residents from other racial and ethnic groups.

More than 80% of Black Altadeneans own their homes – more than double the rate of Black homeownership in California overall.

According to Afro LA News, Altadena Not-For-Sale “has become a rallying cry among residents and grassroots coalitions who are fearful that out-of-town developers will capitalize on the tragedy and reconstruct Altadena into something locals no longer recognize. … The knee-jerk response is, ‘Yeah, we’re gonna rebuild,’ … [but] as insurance settlements start to happen and things sort of settle and the media starts to go away, this reality of, ‘How am I gonna rebuild, and what does that look like?’ That’s where the design professionals can really be of help.”[6]

The coalition’s primary goal is to enable African American families who want to remain there “to retain the generational wealth built through equity in their homes.”

If you can’t recall the sheer devastation caused by these fires, you can access an aerial view of parts of Altadena - HERE.

The Altadena coalition exemplifies the collective effort to preserve Black wealth.

A Bold Bipartisan Response to America’s Housing Crisis

I published three newsletters in January that discussed America’s housing affordability crisis and what actions need to be taken. Then Trump was elected, and many of these proposed strategies had to be postponed.

However, there is some potentially good news from, of all places, Congress, on this front. The quote below is from a blog post by Shaun Donovan, CEO of Enterprise Community Partners, a national non-profit partner in the Purple Line Corridor Coalition (PLCC). I have consulted with the PLCC about equitable development and redevelopment strategies over the past eight years.

Shaun Donovan, Enterprise’s CEO and president, writes that

“the introduction of the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act represents a critical step toward addressing the housing supply crisis that impacts communities of all sizes—urban, suburban, and rural alike, By expanding and strengthening the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, this legislation will help build and preserve hundreds of thousands of affordable homes, making a meaningful difference in the lives of families, seniors, and individuals across the country. …With more than 100 bipartisan cosponsors from more than 30 states, the bill's strong support reflects a consensus that transcends partisanship and affirms that increasing the supply of affordable homes is a nationwide necessity."[7]

Remarkably, this Act was put forth by over 100 bipartisan cosponsors — “a record-setting show of early support that surpasses the previous high of 66 original cosponsors in the 118th Congress. A companion bill in the Senate is expected to be introduced later this month or early May.”[8]

For a century and a half, African Americans have been disproportionately affected by the U.S. justice system. A wide range of substantial reforms is necessary to change that equation. Even small steps matter – here are two: one on jail debt, the other on expungement reform.

A Burden Lifted: Why One County Wiped Out Millions in Jail Debt

Last fall, a Pennsylvania jurisdiction, Dauphin County, did something almost unheard of: it forgave more than $60 million in debt owed by formerly incarcerated people and their families to the county.

What specifically does it erase? The so-called pay-to-stay fees were charged to people as they sat in jail awaiting trial.

How long are these pre-trial stays? Often, they last as long as a year or two, believe it or not. The county has been charging people by the day. As severe as this sounds, it is common practice in Pennsylvania and, in some form, in 43 out of 50 states across the U.S.

From a racial standpoint, why does this matter?

Clearly, these types of fees and fines in scores of jurisdictions disproportionately impact lower-income individuals and people of color (for whom the rates of arrest, prosecution, and incarceration have always been inequitable). Blacks are disproportionately impacted in the county: they make up 20% of the population, but exceed 50% of the jail population there.[9]

Justice advocates are correct in arguing that these pay-to-stay laws directly hinder individuals' successful reintegration into society, as they already encounter significant challenges for basic survival that are exacerbated by the burden of extreme debts.

“The practice of charging people for their time in lockup is but one contributor to a vast array of fines and fees that extracts money from people at virtually every stage of the criminal legal system — starting with jail booking and often lingering, through probation and parole, for years or decades after someone has been released, and affecting even those charged as children.”

These schemes help fund government operations but “place vulnerable people in financial ruin while often failing to generate sustainable revenue streams.”[10]

Success in a single county is merely a drop in the bucket compared to the justice reform our nation needs. However, it offers a model for towns, cities, counties, and states to follow if justice reform is to be more than mere lip service.

Expungement Reform: A New Maryland Law

In mid-April, my Maryland Governor, Wes Moore, signed the Expungement Reform Act into law, which “expands the types of convictions that can be removed from a person's criminal record”[11] once he or she has completed their sentence (including probation). Expunging would remove a conviction from public court or police records.

Here’s how it would work:

“Under the bill, minor traffic crimes, some misdemeanors like alcohol or cannabis offenses, and some domestic-related offenses can be expunged from a person's record. Some felonies, like the distribution of cannabis, could also be expunged under certain circumstances.”[12]

In most cases, a person can request that a conviction be expunged five years after completing their sentence or paying restitution.

However, for crimes related to domestic matters, a person must wait 15 years to file an expungement request. For felonies, a person needs to wait seven years after completing their sentence.

The state's attorney or a victim can object to the expungement; in that case, a court must hold a hearing before accepting or rejecting the request.

“A conviction would not be eligible for expungement if the person is awaiting a trial or conviction for another crime.”[13]

Rutgers University (NJ) Plans to Take on Trump

This story is good news, quite different from all the above. It emphasizes the importance of collective resistance and, ultimately, collective action in this time.

President Tr*mp has already threatened Columbia and Harvard (among other universities) that their federal grant funding is at risk unless they eliminate DEI programs and comply with the administration’s mandates that jeopardize free speech on campus and research affecting the nation’s well-being.

Two Rutgers University professors in New Jersey recently drafted a

“one-page ‘mutual defense compact.’ It was a one-for-all, all-for-one statement of solidarity among schools in the Big Ten athletic and academic conference — 18 large, predominantly public universities that together enroll roughly 600,000 students each year.” Their compact indicated that if one university’s rights are infringed, it shall be considered an infringement against all.”[14]The compact has been approved by faculty senates in over a dozen institutions; however, it still lacks the support of the administrators or boards of those universities. Participating schools would be asked to commit to making a “unified and vigorous response” when member universities face “direct political or legal infringement.” Faculty members might, for example, be asked to provide legal services, strategic communication, or expert testimony.

The momentum behind this faculty movement extends beyond anti-DEI orders; it follows the National Science Foundation's cancellation of over 400 research awards to numerous research institutions and the National Institutes of Health's cancellation of nearly 800 grants for biomedical research.

Beyond the ‘Big Ten’ league of institutions to which Rutgers belongs, along with the likes of Ohio State University, the University of Michigan, and the University of Washington, other major university senates have joined the cause, including the University of Massachusetts, the State University of New York, and three schools that are part of the City University of New York.

Finally, after Harvard sued the federal government in April, 500 universities have signed a joint statement opposing “government overreach and political interference now endangering American higher education.”[15]

Harvard’s lawsuit is one of more than 250 filed against the administration since January, with the majority initiated by the ACLU, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Common Cause, Public Citizen, and the American Federation of Government Employees, among others.

Finally, this is a story about several cases that focus on Tr*mp's attempts to withhold school funding from any school system or institution that continues to implement “DEI” practices, as well as the actions being taken to block the administration.

3 Courts Thwart Trump from Withholding School Funds Over DEI

In all three cases, federal judges issued rulings to pause the withholding of funds related to diversity and equity. Tr*mp’s threat is to refuse to fund billions of dollars in Title I money that “pay for teachers, counselors and academic programs in schools that serve low-income children.”[16] The administration’s Education Department demanded that all 50 state education agencies attest in writing that their schools do not use certain D.E.I. practices and should end programs that serve racial groups.

More or less, all three judges made the same argument for the pause: the administration has set “no clear boundaries” (said one judge) or had not provided a sufficiently detailed definition of DEI to warrant such drastic cuts. Another judge said the “policy threatened to restrict free speech in the classroom, while overstepping the executive branch’s legal authority over local schools. … and would cripple the operations of many educational institutions.”[17]

Many legal scholars—those for and against what Tr*mp is doing—believe these cases will ultimately reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

Let’s hope the court holds to precedent and upholds current law.

Footnotes

[1] Lyneir Richardson, “A Playbook to Buy Back the Block: How Community Practitioners Can Foster Inclusive Ownership of Commercial Real Estate,” The Brookings Institution, July 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/BBtB-playbook-final-july-11-2024.pdf.

[2] Andre Perry, “What’s going right about Black life? The Black Progress Index tells us what, where, and how,” The Emancipator, September 27, 2022, https://theemancipator.org/2022/09/27/topics/money/whats-going-right-about-black-life-black-progress-index-tells-us-what-where-how/.

[3] Andre M. Perry and Jonathan Rothwel, “The Black Progress Index: Examining the social factors that influence Black well-being,” The Brookings Institution, September 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-black-progress-index/.

[4] “Guaranteed Income: A Primer for Funders,” Economic Security Project, May 16, 2022, https://economicsecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/220516-Funder-Primer.pdf.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Corinne Ruff, “These Black architects are helping rebuild Altadena after L.A. wildfires,” Afro L.A., April 23, 2025, https://afrolanews.org/2025/04/these-black-architects-are-helping-rebuild-altadena-after-l-a-wildfires/

[7] Ayrianne Parks, “The Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act of 2025: A Bold Bipartisan Response to America’s Housing Crisis,” Enterprise Community Partners, April 9, 2025, https://enterprisecommunity.org/blog/affordable-housing-credit-improvement-act-2025.

[8] Ibid

[9] Alex Burness, “A Burden Lifted: Why One County Wiped Out Millions in Jail Debt,” reasons to be cheerful, April 25, 2025, https://reasonstobecheerful.world/pennsylvania-county-wiped-out-millions-in-jail-debt/

[10] Ibid.

[11] JT Moodee Lockman, “New Maryland laws include expungement reform, increased support for federal workers,” WJZ News/CBS News, April 22, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/baltimore/news/maryland-legislation-expunge-criminal-record-federal-workers-funding/

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Tracey Tully, “This State University Has a Plan to Take on Trump,” The New York Times, April 30, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/30/nyregion/rutgers-mdc-big-10.html.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Dana Goldstein, “Courts Block Trump From Withholding School Funds Over D.E.I., for Now,” The New York Times, April 24, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/24/us/trump-public-school-funds-dei.html.

[17] Ibid.